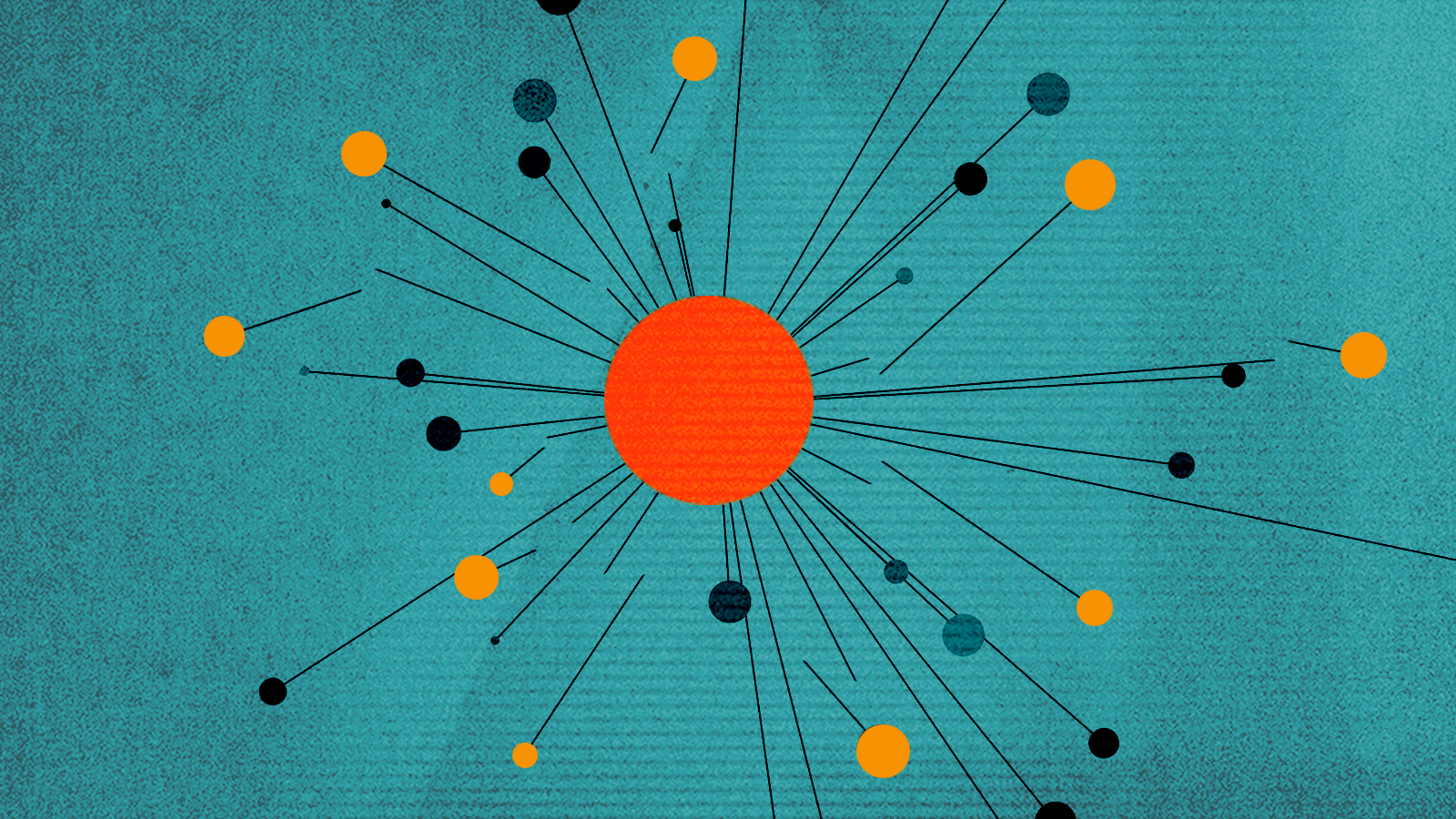

An interwoven shadow fleet is enabling the shipment of Iranian, Russian and Venezuelan petroleum despite international sanctions, a Kharon investigation has found.

The fleet is operated by a network of ship owners, facilitators and management companies, with three Indian nationals at the center. These entities, though largely not sanctioned, appear to be transporting restricted goods through shell companies.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury this month sanctioned a different international maritime network for facilitating the shipping of Iranian crude oil worth hundreds of millions of dollars to China. It marked the United States’ first major measure since President Trump announced he was renewing a “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran, to hamper its ability to obtain nuclear weapons.

It also could signal more U.S. scrutiny against such networks.

For context: The first Trump administration issued guidance in May 2020 that addressed illicit shipping and sanctions-evasion practices for the maritime industry and the energy and metals sectors.

The advisory listed a number of red flags that relevant business sectors, including shipping, insurance and port operators, should watch for as indicators of deceptive shipping practices, including:

Inside the network: Operated by 12 interconnected companies, the shadow fleet’s ships leverage opaque jurisdictions such as Mauritius and the Seychelles, whose corporate registries do not publicly reveal beneficial ownership information. This lack of transparency makes it harder to identify affiliations with sanctioned entities and illicit trade.

Three Indian nationals—Maria Consaline Thasan, Ulaganathan Gopala Krishnan, and Kudiyarasu Thamizharasan—direct the maritime companies, which are based in India, Hong Kong and the UAE.

Only one of the 12 companies is sanctioned: the UAE-based Harry Victor Ship Management & Operation LLC, which Thasan manages. The U.S. designated it in October for facilitating transactions on behalf of Triliance Petrochemical Co. Limited, a major player in Iran’s illicit oil exports. Three of Harry Victor Ship’s vessels—the GOODWIN, ANHONA, and WEN YAO—were also sanctioned.

Three weeks after its designation, the GOODWIN changed its name to the CUME and falsified its flag to Guyana’s.

Connect the dots: The transfer of vessel ownership, management and registration across jurisdictions lets sanctioned entities and vessels continue to operate under ever-changing identities.

Take Ravel Ship Management, which is directed by Thasan and Thamizharasan and does not currently manage any vessels. The most recent vessel under its management was the ELVA, which since October 2023 has been managed by the Pakistan-based Inaya Ship Management Pvt Ltd. Inaya’s owner, in turn, is the Seychelles-based Lufindo Holding Limited.

The U.S. sanctioned those two companies and the ELVA in December for their role in Iran’s network of shadow fleet tankers and ship-management firms that transported Iranian oil to overseas customers in violation of U.S. sanctions. And while Ravel Ship Management may no longer operate the sanctioned vessel, it shares a phone number and address with Lufindo Holding Limited, demonstrating a clear material tie.

The fleet is operated by a network of ship owners, facilitators and management companies, with three Indian nationals at the center. These entities, though largely not sanctioned, appear to be transporting restricted goods through shell companies.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury this month sanctioned a different international maritime network for facilitating the shipping of Iranian crude oil worth hundreds of millions of dollars to China. It marked the United States’ first major measure since President Trump announced he was renewing a “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran, to hamper its ability to obtain nuclear weapons.

It also could signal more U.S. scrutiny against such networks.

For context: The first Trump administration issued guidance in May 2020 that addressed illicit shipping and sanctions-evasion practices for the maritime industry and the energy and metals sectors.

The advisory listed a number of red flags that relevant business sectors, including shipping, insurance and port operators, should watch for as indicators of deceptive shipping practices, including:

- Ship-to-ship transfers.

- False flags and flag-hopping.

- Complex ownership or management structures, including utilizing shell entities.

Inside the network: Operated by 12 interconnected companies, the shadow fleet’s ships leverage opaque jurisdictions such as Mauritius and the Seychelles, whose corporate registries do not publicly reveal beneficial ownership information. This lack of transparency makes it harder to identify affiliations with sanctioned entities and illicit trade.

Three Indian nationals—Maria Consaline Thasan, Ulaganathan Gopala Krishnan, and Kudiyarasu Thamizharasan—direct the maritime companies, which are based in India, Hong Kong and the UAE.

Only one of the 12 companies is sanctioned: the UAE-based Harry Victor Ship Management & Operation LLC, which Thasan manages. The U.S. designated it in October for facilitating transactions on behalf of Triliance Petrochemical Co. Limited, a major player in Iran’s illicit oil exports. Three of Harry Victor Ship’s vessels—the GOODWIN, ANHONA, and WEN YAO—were also sanctioned.

Three weeks after its designation, the GOODWIN changed its name to the CUME and falsified its flag to Guyana’s.

Connect the dots: The transfer of vessel ownership, management and registration across jurisdictions lets sanctioned entities and vessels continue to operate under ever-changing identities.

Take Ravel Ship Management, which is directed by Thasan and Thamizharasan and does not currently manage any vessels. The most recent vessel under its management was the ELVA, which since October 2023 has been managed by the Pakistan-based Inaya Ship Management Pvt Ltd. Inaya’s owner, in turn, is the Seychelles-based Lufindo Holding Limited.

The U.S. sanctioned those two companies and the ELVA in December for their role in Iran’s network of shadow fleet tankers and ship-management firms that transported Iranian oil to overseas customers in violation of U.S. sanctions. And while Ravel Ship Management may no longer operate the sanctioned vessel, it shares a phone number and address with Lufindo Holding Limited, demonstrating a clear material tie.

Kharon users can explore this Insight in greater detail through the ClearView platform.

Further illustrating the shadow fleet’s interconnected nature, Ravel Ship Management shares leadership with Vika Line Marine Services, which operates the UDAYA, a vessel that the U.K. sanctioned in December for transporting Russian oil.

Kharon users can explore this Insight in greater detail through the ClearView platform.

Venezuela comes into play in another corner of the network involving Chola Gas Shipping, which was once directed by Thasan and now is overseen by Thamizharasan and Krishnan. Chola Gas Shipping is the operator of one vessel, the ALMA, whose owner shares an address with Sisalana Technik Limited, an Istanbul-based entity.

According to U.S. court documents, three vessels operated by Sisalana Technik Limited facilitated the export of Venezuelan oil for the benefit of Venezuela's largest state-owned oil company, PDVSA. The U.S. sanctioned PDVSA in 2019.

Takeaways: This intricate and ever-shifting network underscores the challenge that regulators and private industry face in enforcing and navigating sanctions against Iran’s, Russia’s and Venezuela’s shadow fleets and evasion networks.

Such complexities require deeper digging. The May 2020 U.S. maritime guidance recommends that if private sector entities cannot reasonably identify the actual person or organizations involved in the transaction, they may wish to consider performing additional due diligence.

There are a few key steps that those in relevant business sectors should take to identify the potential risk of sanctions evasion:

According to U.S. court documents, three vessels operated by Sisalana Technik Limited facilitated the export of Venezuelan oil for the benefit of Venezuela's largest state-owned oil company, PDVSA. The U.S. sanctioned PDVSA in 2019.

Takeaways: This intricate and ever-shifting network underscores the challenge that regulators and private industry face in enforcing and navigating sanctions against Iran’s, Russia’s and Venezuela’s shadow fleets and evasion networks.

Such complexities require deeper digging. The May 2020 U.S. maritime guidance recommends that if private sector entities cannot reasonably identify the actual person or organizations involved in the transaction, they may wish to consider performing additional due diligence.

There are a few key steps that those in relevant business sectors should take to identify the potential risk of sanctions evasion:

- Screen the addresses of your party of interest. Sharing an address or having an address similar to that of a sanctioned party is considered a red flag indicator of sanctions evasion.

- Keep in mind that vessels will change their names and flags, so use the IMO number—a unique ship identifier issued by the International Maritime Organization—rather than the vessel name when screening against lists.

- Remember that a vessel is just the starting point. Maritime trade may center on one ship, but related vessels and actors within the maritime industry can expose you to sanctions-related risk, too.