Between 2011 and 2014, military officials from Beijing stationed observers inside a materials-science lab at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China’s self-styled MIT. They shadowed researchers “wherever you went,” lead scientist Wu Guohua later recalled, monitoring every experiment, every setback, every incremental advance.

The lab’s assignment from the People’s Liberation Army was urgent and its challenge steep: developing parts for an aircraft lightweight enough to fly at five times the speed of sound, fast enough to evade U.S. defenses and strike naval carriers before they could respond.

“At first, we reported progress once a month, then once a week, and eventually every day,” Wu said, in an interview with a Chinese state-run scientific journal reviewed by Kharon. “Even that did not satisfy the aerospace officials.”

The lab’s high-stakes hypersonic project, which has not previously been reported in Western media, ended in success, producing a scientific breakthrough that Wu said contributed to China’s successful test of a hypersonic missile vehicle in early 2014.

All the while, without disclosing that parallel military work, the SJTU lab and its researchers had for years been working with a joint engineering institute their school ran with the University of Michigan, partnering on a research center with General Motors, and collaborating with a host of other researchers and institutions in the U.S., Europe and Australia. The lab’s military work, like some of its Western collaboration, appears to be ongoing.

The lab’s assignment from the People’s Liberation Army was urgent and its challenge steep: developing parts for an aircraft lightweight enough to fly at five times the speed of sound, fast enough to evade U.S. defenses and strike naval carriers before they could respond.

“At first, we reported progress once a month, then once a week, and eventually every day,” Wu said, in an interview with a Chinese state-run scientific journal reviewed by Kharon. “Even that did not satisfy the aerospace officials.”

The lab’s high-stakes hypersonic project, which has not previously been reported in Western media, ended in success, producing a scientific breakthrough that Wu said contributed to China’s successful test of a hypersonic missile vehicle in early 2014.

All the while, without disclosing that parallel military work, the SJTU lab and its researchers had for years been working with a joint engineering institute their school ran with the University of Michigan, partnering on a research center with General Motors, and collaborating with a host of other researchers and institutions in the U.S., Europe and Australia. The lab’s military work, like some of its Western collaboration, appears to be ongoing.

SJTU lab director Ding Wenjiang (at left, in white) talks to the late Xu Qiliang (center, in blue), vice chairman of the Central Military Commission and general of the PLA Air Force, at an undated gathering of uniformed senior military leaders. Also in attendance is SJTU professor Wu Guohua (back left, in brown). (Screengrab via 2023 LAF Center promotional video)

The University of Michigan’s partnership, one of the longest-running U.S.-China collaborations in engineering and materials science, ended in January, after months of congressional scrutiny and federal investigations under the new Trump administration into foreign influence at U.S. universities. In a statement on the breakup, then-Michigan President Santa J. Ono had cited “our commitment to national security,” without offering details.

The case of the SJTU lab, experts said, highlights a growing risk for Western universities: Scientific collaborations that appear purely academic may, in practice, help to fuel China’s military advancements, at the United States’ expense.

“Even if an individual [Chinese] researcher isn't interested in military applications, the university is,” said Jeffrey Stoff, founder and president of the Northern Virginia-based Center for Research Security & Integrity. “They want to collaborate globally and attract top talent, but any work they do abroad must ultimately serve the state's strategic goals: modernizing the military and dominating critical technologies.”

The case of the SJTU lab, experts said, highlights a growing risk for Western universities: Scientific collaborations that appear purely academic may, in practice, help to fuel China’s military advancements, at the United States’ expense.

“Even if an individual [Chinese] researcher isn't interested in military applications, the university is,” said Jeffrey Stoff, founder and president of the Northern Virginia-based Center for Research Security & Integrity. “They want to collaborate globally and attract top talent, but any work they do abroad must ultimately serve the state's strategic goals: modernizing the military and dominating critical technologies.”

China’s network of feeder universities for defense has expanded in recent years, folding dozens of institutions under the same state agency that oversees the country’s military-industrial complex. SJTU, which has long straddled the line between civilian research and military ambitions, is among that group.

Kharon’s review of Chinese-language research papers, patents, procurement filings and corporate records also traced the work of the key SJTU lab, the National Engineering Research Center of Light Alloy Net Forming (or LAF Center), out into a network of companies that commercialize academic breakthroughs for Chinese military use.

SJTU and its press director did not respond to emailed questions about the LAF Center’s hypersonic project, the university’s broader collaboration with China’s military or its Western partnerships.

The U.S. has issued increasing volumes of guidance about research security in recent years, but it has not instituted hard and fast regulations governing foreign collaborations. That leaves schools to police ties on their own, experts said, often without the resources or resolve to do so.

For “the Chinese, it’s all integrated: academic, commercial, military,” William LaPlante, the Pentagon’s former acquisition chief, said at an event in Washington last month. “They don’t distinguish that. It’s a mentality that we don’t have.”

Which leads to risks, like those from SJTU’s lab, that universities don’t see.

Helping German automakers localize production in China, Ding was introduced to magnesium alloys, lighter and stronger than aluminum and widely used in European cars. “At that time, no one in China was researching magnesium,” Ding told Pujiang Zongheng, a state-owned magazine, in 2014.

He pivoted his entire research program. In 2000, the work had grown significant enough for SJTU to establish his lab as the LAF Center, backed by the state, with Ding as director. He brought in Wu, an expert in foundry technology. From this point forward, the lab would straddle two tracks.

In 2005, the University of Michigan and SJTU announced their joint institute, offering degrees in mechanical engineering, electrical and computer engineering, and, later, materials science and engineering. “Cultural and economic globalization is our shared future,” Michigan’s then-president, Mary Sue Coleman, wrote at the time. The partnership, she said, would create “global leaders who can translate our political and economic systems to their home countries.” (The University of Michigan did not respond to emailed questions about SJTU’s military work or the schools’ collaboration.)

Several months later, a review of school and media records found, Ding took a second position that wouldn’t appear in any press release, becoming chief scientist for a major national research project under the PLA’s General Armament Department. That project’s stated focus was on “High-Performance Magnesium Alloys for Future Weapons and Equipment Applications.”

Kharon’s review of Chinese-language research papers, patents, procurement filings and corporate records also traced the work of the key SJTU lab, the National Engineering Research Center of Light Alloy Net Forming (or LAF Center), out into a network of companies that commercialize academic breakthroughs for Chinese military use.

SJTU and its press director did not respond to emailed questions about the LAF Center’s hypersonic project, the university’s broader collaboration with China’s military or its Western partnerships.

The U.S. has issued increasing volumes of guidance about research security in recent years, but it has not instituted hard and fast regulations governing foreign collaborations. That leaves schools to police ties on their own, experts said, often without the resources or resolve to do so.

For “the Chinese, it’s all integrated: academic, commercial, military,” William LaPlante, the Pentagon’s former acquisition chief, said at an event in Washington last month. “They don’t distinguish that. It’s a mentality that we don’t have.”

Which leads to risks, like those from SJTU’s lab, that universities don’t see.

Collaboration abroad, hypersonic at home

The LAF Center’s path to military prominence began decades before its Western partnerships. In the 1980s, researcher Ding Wenjiang tested aluminum alloys for torpedo casings at a defense lab under SJTU's School of Materials Science, winning a national defense award in 1988. But a civilian project soon reshaped his work.Helping German automakers localize production in China, Ding was introduced to magnesium alloys, lighter and stronger than aluminum and widely used in European cars. “At that time, no one in China was researching magnesium,” Ding told Pujiang Zongheng, a state-owned magazine, in 2014.

He pivoted his entire research program. In 2000, the work had grown significant enough for SJTU to establish his lab as the LAF Center, backed by the state, with Ding as director. He brought in Wu, an expert in foundry technology. From this point forward, the lab would straddle two tracks.

In 2005, the University of Michigan and SJTU announced their joint institute, offering degrees in mechanical engineering, electrical and computer engineering, and, later, materials science and engineering. “Cultural and economic globalization is our shared future,” Michigan’s then-president, Mary Sue Coleman, wrote at the time. The partnership, she said, would create “global leaders who can translate our political and economic systems to their home countries.” (The University of Michigan did not respond to emailed questions about SJTU’s military work or the schools’ collaboration.)

Several months later, a review of school and media records found, Ding took a second position that wouldn’t appear in any press release, becoming chief scientist for a major national research project under the PLA’s General Armament Department. That project’s stated focus was on “High-Performance Magnesium Alloys for Future Weapons and Equipment Applications.”

How we reported this story:

Much of the SJTU lab’s military research is chronicled only in Chinese-language sources, where key terms like “weapon,” “defense,” or “equipment” are often omitted or disguised. A Kharon investigation reconstructed the lab’s role in hypersonic projects by cross-referencing academic journals, papers, media interviews and publicly reported awards.

“It’s not surprising to me that this Chinese university … would be collaborating with the University of Michigan—then, and probably still, the U.S. center of magnesium-alloy research, though largely focused on automotive applications,” said Cameron Tracy, a senior research scholar at UC Berkeley’s Risk and Security Lab in the Goldman School of Public Policy.

“Developing a better, strong, light metal—you can use it for weapons. You can also use it for so much other stuff, like cars, laptops or smartphones,” said Tracy, who earned his own Ph.D. in materials science from Michigan. “That dual-use nature makes it hard to determine intent solely from the research.”

Between 2005 and 2009, according to Shanghai science publications, the SJTU lab carried out several PLA projects. It also struck a $4 million research partnership, in 2008, with General Motors, itself a longtime University of Michigan partner, that focused on advanced manufacturing and lightweight materials, according to Chinese government and SJTU press releases at the time. Chinese state media called Ding the director and a founding member of the initiative, known as the GM-SJTU Institute of Automotive Research.

Asked about that research collaboration and the lab’s military work, GM sent a statement saying their “Joint work on vehicle lightweighting ended in 2016.”

“Developing a better, strong, light metal—you can use it for weapons. You can also use it for so much other stuff, like cars, laptops or smartphones,” said Tracy, who earned his own Ph.D. in materials science from Michigan. “That dual-use nature makes it hard to determine intent solely from the research.”

Between 2005 and 2009, according to Shanghai science publications, the SJTU lab carried out several PLA projects. It also struck a $4 million research partnership, in 2008, with General Motors, itself a longtime University of Michigan partner, that focused on advanced manufacturing and lightweight materials, according to Chinese government and SJTU press releases at the time. Chinese state media called Ding the director and a founding member of the initiative, known as the GM-SJTU Institute of Automotive Research.

Asked about that research collaboration and the lab’s military work, GM sent a statement saying their “Joint work on vehicle lightweighting ended in 2016.”

The GM–SJTU Institute of Automotive Research holds a signing ceremony in Shanghai on March 4, 2008. Ding Wenjiang, back row, second from left, took part in the event, as did two GM executives. (SJTU newspaper)

It was in 2011 that the LAF Center received the assignment that would elevate its work to a new level of national importance and secrecy. According to Chinese government journals, Wu’s interviews and media reports, defense officials approached the lab with a classified “national major project” to develop structural components for a hypersonic glide vehicle.

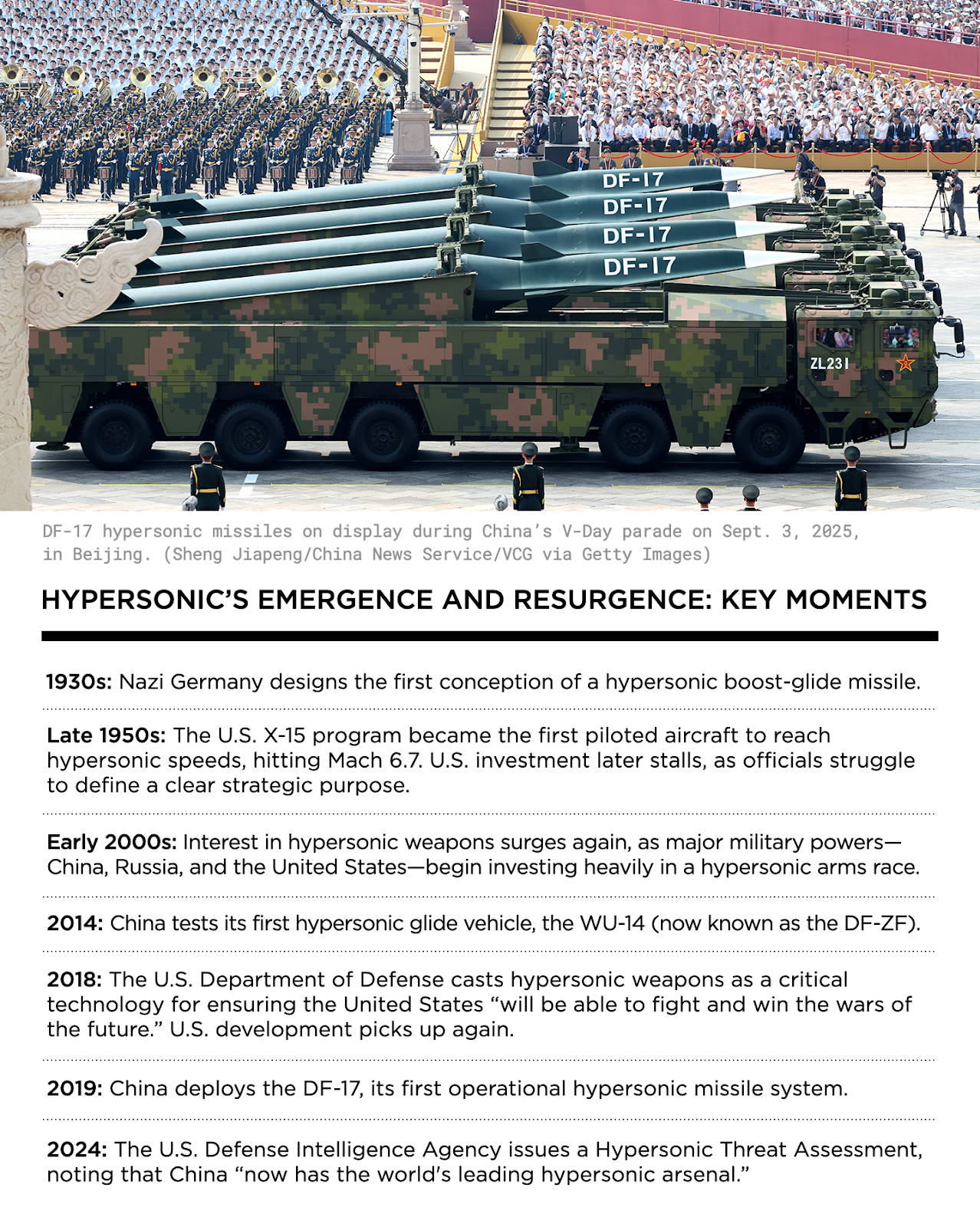

Hypersonic weapons represent China’s most serious challenge to U.S. dominance in the Pacific, analysts say, and Beijing has made them an increasing strategic priority accordingly. Traveling at Mach 5 or faster, hypersonic missiles can maneuver unpredictably, making them very difficult for aircraft carriers or bases to intercept.

“There’s only one use for hypersonics that China has, and that’s military,” Stoff said. That research is “directly helping the PLA.”

Hypersonic weapons represent China’s most serious challenge to U.S. dominance in the Pacific, analysts say, and Beijing has made them an increasing strategic priority accordingly. Traveling at Mach 5 or faster, hypersonic missiles can maneuver unpredictably, making them very difficult for aircraft carriers or bases to intercept.

“There’s only one use for hypersonics that China has, and that’s military,” Stoff said. That research is “directly helping the PLA.”

According to Wu’s account, he and Ding marshalled more than 100 scientists at the lab toward their project, including senior researchers, postdoctoral fellows, doctoral students and experimental staff. By early 2014, Wu reported, they had cut more than 100 kilograms from the aircraft’s original design and contributed to the successful hypersonic flight test. The project's chief commander, he said, traveled that March from Beijing to Shanghai to deliver them a letter of gratitude personally.

The same month, 7,000 miles away in New York, the UM-SJTU Joint Institute received the Institute of International Education's “Best Practices in International Partnerships” award. After eight years of collaboration, with thousands of students having enrolled, the institute vowed to serve as “a springboard for collaborative research in fields of strategic interest to both the U.S. and China.”

Tracy said he had not been aware of Michigan’s joint program with SJTU during his time there. But he observed that it reflected a different era in U.S.-China relations, when global scientific engagement was celebrated and encouraged.

“If you look at any STEM field 10 years ago, a large number of highly skilled postdocs in the U.S. were from China,” he said. “Losing access to that talent today has slowed scientific productivity in many fields. Some argue it's necessary for national security. Others say it hinders scientific advancement. Both perspectives have merit.”

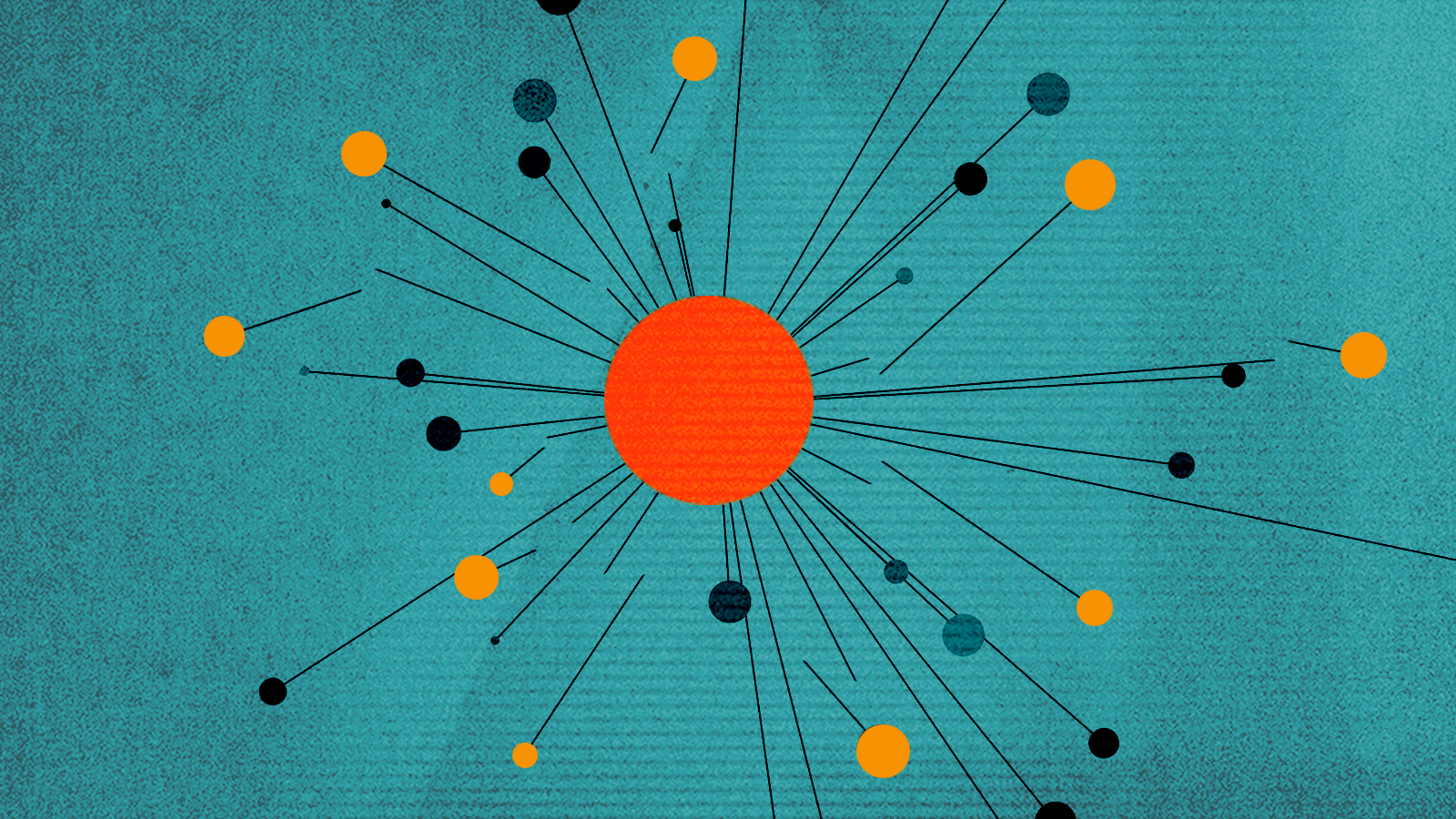

“China is very adept at turning research into usable technology,” Stoff said, pointing to “hundreds of state-backed centers [that] connect universities, research institutes, and enterprises.”

“U.S. universities focus on fundamental research,” he said. “China prioritizes applied outcomes.”

The same month, 7,000 miles away in New York, the UM-SJTU Joint Institute received the Institute of International Education's “Best Practices in International Partnerships” award. After eight years of collaboration, with thousands of students having enrolled, the institute vowed to serve as “a springboard for collaborative research in fields of strategic interest to both the U.S. and China.”

Tracy said he had not been aware of Michigan’s joint program with SJTU during his time there. But he observed that it reflected a different era in U.S.-China relations, when global scientific engagement was celebrated and encouraged.

“If you look at any STEM field 10 years ago, a large number of highly skilled postdocs in the U.S. were from China,” he said. “Losing access to that talent today has slowed scientific productivity in many fields. Some argue it's necessary for national security. Others say it hinders scientific advancement. Both perspectives have merit.”

Research’s flow: From the lab to China’s military complex

Production out of the LAF Center appears to have ramped up after its hypersonic milestone. In a 2017 paper titled “High-Performance Magnesium-Rare Earth Alloys and Their Military Applications,” Ding and Wu wrote that the project had produced more than 30 different large, complex components for key defense programs in all, including:- triangle-shaped wings for the hypersonic aircraft.

- mechanical housings for Z-20 military helicopters.

- housing for “a certain anti-tank missile, which has been transferred to mass production.”

- components for China’s HQ‑16 air‑defense system and YJ‑21 hypersonic anti-ship missiles, both of which, Ding and Wu wrote, had “entered mass production” as well.

“China is very adept at turning research into usable technology,” Stoff said, pointing to “hundreds of state-backed centers [that] connect universities, research institutes, and enterprises.”

“U.S. universities focus on fundamental research,” he said. “China prioritizes applied outcomes.”

YJ-21 missiles on display during a military parade Sept. 3 in Beijing. Ding and Wu wrote that their hypersonic work had produced components for YJ-21s that had since “entered mass production.” (Lu Jinbo/Xinhua via Getty Images)

The applied outcomes of the LAF Center’s research funnel through a similarly named corporate twin 15 miles away: Shanghai Light Alloy Precision Forming National Engineering Research Center Co., Ltd., which, according to the university’s website, serves as the lab’s “industrial arm,” “providing strong support for the country's major strategic products.”

The company, which SJTU created soon after the lab’s own founding, has since expanded to four locations across China. The Fengyang branch, Fengyang LS Light Alloy Precise Forming Co., offers a view into how the lab’s commercial network operates.

According to corporate records, Fengyang LS lists Ding as its founder and a 20% shareholder; Peng Liming, the lab’s deputy director, serves as chief technologist. On its website, the company says it “relies entirely on the SJTU Light Alloy Precision Forming National Engineering Research Center.”

The company, which SJTU created soon after the lab’s own founding, has since expanded to four locations across China. The Fengyang branch, Fengyang LS Light Alloy Precise Forming Co., offers a view into how the lab’s commercial network operates.

According to corporate records, Fengyang LS lists Ding as its founder and a 20% shareholder; Peng Liming, the lab’s deputy director, serves as chief technologist. On its website, the company says it “relies entirely on the SJTU Light Alloy Precision Forming National Engineering Research Center.”

China’s defense industry depends on Fengyang LS in turn. The company holds three military-industry licenses—the credentials required for weapons manufacturing and development—and its site says it partners with some of China’s largest defense conglomerates. Among them are at least seven that the U.S. Defense Department has designated as Chinese military companies:

The corporate network extends beyond the lab’s direct spin-offs, too, Kharon found. Through a 2019 LAF Center partnership, Ding also became chief technology expert for Guangdong Hongtu Technology, a publicly traded automotive manufacturer. According to corporate filings, the company later invested $17.8 million in a subsidiary of the Aviation Industry Corporation of China.

In 2018, Ding’s team partnered with an Australian public research university on corrosion-resistant alloys and co-authored research on fuel cells, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, with the U.S. Argonne National Laboratory. Ding then presented his fuel-cell work at Beijing’s Military-Civil Fusion Expo, an event organized by the Central Military Commission.

By 2022, UM-SJTU students were co-authoring further papers with Ding on fuel cells, while the lab’s website simultaneously spotlighted its work on the PLA’s next-generation helicopter.

- Aviation Industry Corporation of China, a maker of airliners, fighter jets, bombers and drones.

- Aero Engine Corporation of China, a maker of military fighter jet engines.

- China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation, a manufacturer of defense products, including missiles.

- the China State Shipbuilding Corporation, the key builder for the PLA Navy of naval vessels, including aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines.

- China North Industries Group, which produces tanks and artillery.

- China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, a supplier of high-performance radar and other military electronics to the People’s Liberation Army.

- SZ DJI Technology Corporation, commonly described as the world’s largest drone manufacturer.

The corporate network extends beyond the lab’s direct spin-offs, too, Kharon found. Through a 2019 LAF Center partnership, Ding also became chief technology expert for Guangdong Hongtu Technology, a publicly traded automotive manufacturer. According to corporate filings, the company later invested $17.8 million in a subsidiary of the Aviation Industry Corporation of China.

A debate over research-security ‘red lines’

The dangers of international collaborations, Stoff said, lie less in what’s ultimately printed in journals than in the lasting “practical expertise” that Chinese researchers can gain from their Western counterparts, “the materials, process knowledge and systems integration.”In 2018, Ding’s team partnered with an Australian public research university on corrosion-resistant alloys and co-authored research on fuel cells, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, with the U.S. Argonne National Laboratory. Ding then presented his fuel-cell work at Beijing’s Military-Civil Fusion Expo, an event organized by the Central Military Commission.

By 2022, UM-SJTU students were co-authoring further papers with Ding on fuel cells, while the lab’s website simultaneously spotlighted its work on the PLA’s next-generation helicopter.

Professor Wu Guohua (third from right in front row) poses with LAF Center technicians during filming for its 2023 promotional video. (Screengrab via video)

Wu told the China Foundry, a state-owned scientific journal, later that year that, despite its advances, “China overall still lags behind developed Western countries” in magnesium-alloy research. Critical materials, such as casting technologies, still came from foreign suppliers.

“China’s advancements [in hypersonic development] have heavily relied on international collaboration,” Stoff said, arguing that it gains “far more than the foreign partner.”

“We absolutely need red lines for collaboration,” he said. “Right now, essentially, there are none.”

But in an October letter last year, the chairman of the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party suggested the University of Michigan had crossed one.

“Shanghai Jiao Tong plays a critical role in the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) military-civil fusion strategy” through “its military-aligned departments and dual-use research programs,” Rep. John Moolenaar (R-Mich.) wrote to Ono. He cited the institution’s 2017 agreement with the PLA’s Strategic Support Force and its contributions to sensitive defense programs, including nuclear weapons and fighter jets.

“China’s advancements [in hypersonic development] have heavily relied on international collaboration,” Stoff said, arguing that it gains “far more than the foreign partner.”

“We absolutely need red lines for collaboration,” he said. “Right now, essentially, there are none.”

But in an October letter last year, the chairman of the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party suggested the University of Michigan had crossed one.

“Shanghai Jiao Tong plays a critical role in the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) military-civil fusion strategy” through “its military-aligned departments and dual-use research programs,” Rep. John Moolenaar (R-Mich.) wrote to Ono. He cited the institution’s 2017 agreement with the PLA’s Strategic Support Force and its contributions to sensitive defense programs, including nuclear weapons and fighter jets.

“Given these concerning developments,” Moolenaar said, “I strongly encourage you to shutter the partnership between U-M and Shanghai Jiao Tong and take the necessary steps to safeguard the integrity of federally funded research at U-M and carefully vet international students studying on U-M’s campus.”

A few months later, Michigan ended the joint institute.

Moolenaar’s broader research-security concerns gained legislative momentum in September, when the House passed the SAFE Research Act. Authored by Moolenaar, it would cut federal funding to U.S. scientists who collaborate with anyone tied to “hostile foreign entities,” with China the primary target.

Faculty members from more than 200 U.S. universities warned that the measure, which they called overly broad and vague, could have “damaging consequences” for “America’s scientific competitiveness, innovation, and ability to attract top global talent.”

Tracy locates the tension in the nature of scientific work itself.

Researchers exhibit “a strong, very ingrained tendency towards universalism, where scientists will often think of themselves not as American scientists or German scientists or Chinese scientists, but as just part of a global or universal community,” he said. “You might just be trying to make a lighter or stronger metal,” without thinking about military applications.

SJTU’s lab made no effort to maintain any such separation in a 2023 Chinese-language promotional video reviewed by Kharon.

Over the course of its 11 minutes, the video by turns:

“Scientific research must not only pursue academic excellence but must serve national strategic needs,” he said in an interview the following year with the state-run Guangming Daily, describing the lab’s guiding philosophy. “China’s science and technology must support the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

A few months later, Michigan ended the joint institute.

Moolenaar’s broader research-security concerns gained legislative momentum in September, when the House passed the SAFE Research Act. Authored by Moolenaar, it would cut federal funding to U.S. scientists who collaborate with anyone tied to “hostile foreign entities,” with China the primary target.

Faculty members from more than 200 U.S. universities warned that the measure, which they called overly broad and vague, could have “damaging consequences” for “America’s scientific competitiveness, innovation, and ability to attract top global talent.”

Tracy locates the tension in the nature of scientific work itself.

Researchers exhibit “a strong, very ingrained tendency towards universalism, where scientists will often think of themselves not as American scientists or German scientists or Chinese scientists, but as just part of a global or universal community,” he said. “You might just be trying to make a lighter or stronger metal,” without thinking about military applications.

SJTU’s lab made no effort to maintain any such separation in a 2023 Chinese-language promotional video reviewed by Kharon.

Over the course of its 11 minutes, the video by turns:

- showcased hypersonic tech and the DF-17 missile, which evolved from the version first tested in 2014, boasting that the lab’s “defense components have been successfully applied to major aerospace and defense projects.”

- promoted joint doctoral programs with Ohio State University and with an Australian university. (In a statement, an Ohio State spokesman said the schools’ joint Ph.D. program had “expired” in December 2018 and that it had “no current, active partnerships” with SJTU.)

- highlighted the lab’s partnerships with companies across the U.S., Japan and Germany.

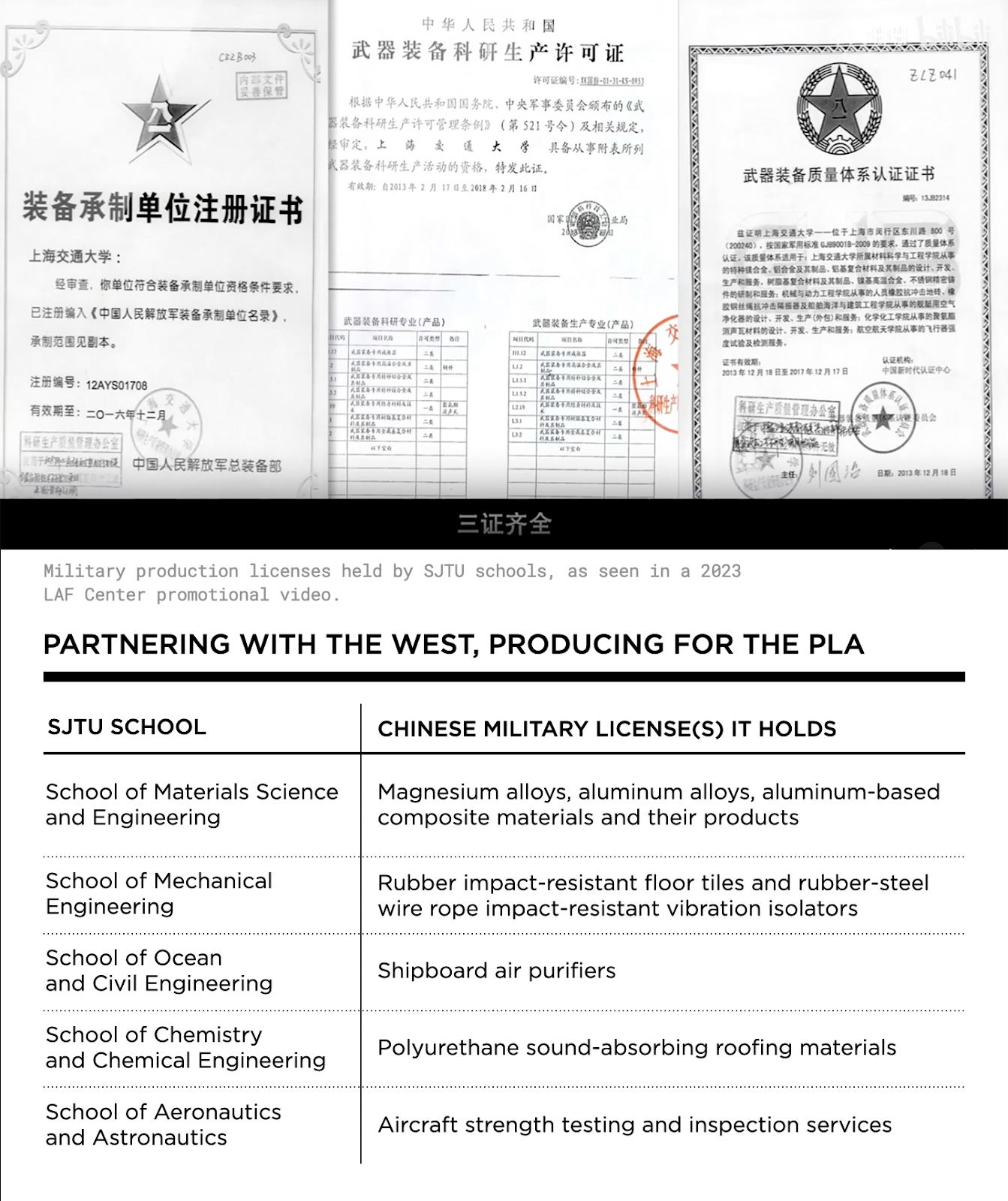

- depicted certificates confirming that the lab held all necessary licenses for working with weapons-grade alloys.

- disclosed that five of SJTU’s schools in total have obtained licenses from China’s defense industry regulator to produce military-grade items.

“Scientific research must not only pursue academic excellence but must serve national strategic needs,” he said in an interview the following year with the state-run Guangming Daily, describing the lab’s guiding philosophy. “China’s science and technology must support the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

Ding (at left, holding red book) leads the lab’s Chinese Communist Party branch during a CCP “Two Studies, One Action” educational activity, which included “studying the Party Constitution and regulations, studying a series of leader’s speeches, and training to become qualified Party members.” (Screengrab via video)

From tech imitation to destination

U.S. agencies agree that China, having achieved operational capability since its 2014 test, now has the world’s leading hypersonic missile arsenal.In a report last year, the Defense Intelligence Agency attributed its leap to “two decades of dramatic advancement through intense and focused investment, development, testing, and deployments in both conventional and nuclear-armed hypersonic technologies.”

Ding traced that strategic evolution himself in September, at an SJTU forum on accelerating technological development. For years, he said, China had prospered through “importing and imitating,” a model that he said had reached its limits.

China’s “technological innovation,” Ding said, “has progressed from a stage of simply following to a new phase of keeping pace and leading.”

His own career reflects that ambition. Ding has expanded now into semiconductors, another strategic priority for Beijing; a company that he founded in 2022 made Chinese headlines this past August for producing “China’s first 28-nanometer critical-dimension electron beam metrology production equipment,” breaking what it called the “long-standing overseas monopoly in chip testing.”

The former UM-SJTU Joint Institute, meanwhile, has rebranded itself, as SJTU Global College. This fall, it announced new partnerships with universities in Canada and Singapore.

Ding’s lab also has pressed ahead, unveiling a joint research center in October with Spain’s IMDEA Materials Institute. The partnership, SJTU promised in a press release, would “actively explore new models of international operation.”

Yu-Jie Liao contributed research to this report.