Forced labor risks in China are shifting, and U.S. enforcement is shifting, too. For months now, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has sharpened its scrutiny of automotive and aerospace shipments, turning it into the most targeted sector under the Uyghur Forced Labor Protection Act (UFLPA).

It’s forcing automakers to redouble and rethink their supply chain due diligence efforts.

“You can’t wait until you’re stopped,” Matt Pohlman, the CEO of the Automotive Industry Action Group (AIAG), said in a fireside-chat webinar with Kharon Director Ethan Woolley last week. “If you wait till you’re stopped, trust me: You’re going to be in trouble.”

What to know: The UFLPA, enacted in 2022, prohibits goods produced in China’s Xinjiang region from entering the U.S. unless there is sufficient evidence that they were not made with forced labor. Companies need to rebut that presumption for their shipments to be released.

If a shipment is detained under the UFLPA, Woolley explained in the webinar, CBP does not inform the company which supplier in their chain is the source of the problem. Instead, that’s up to companies to investigate themselves—and they have limited time to make their case to get their shipment released.

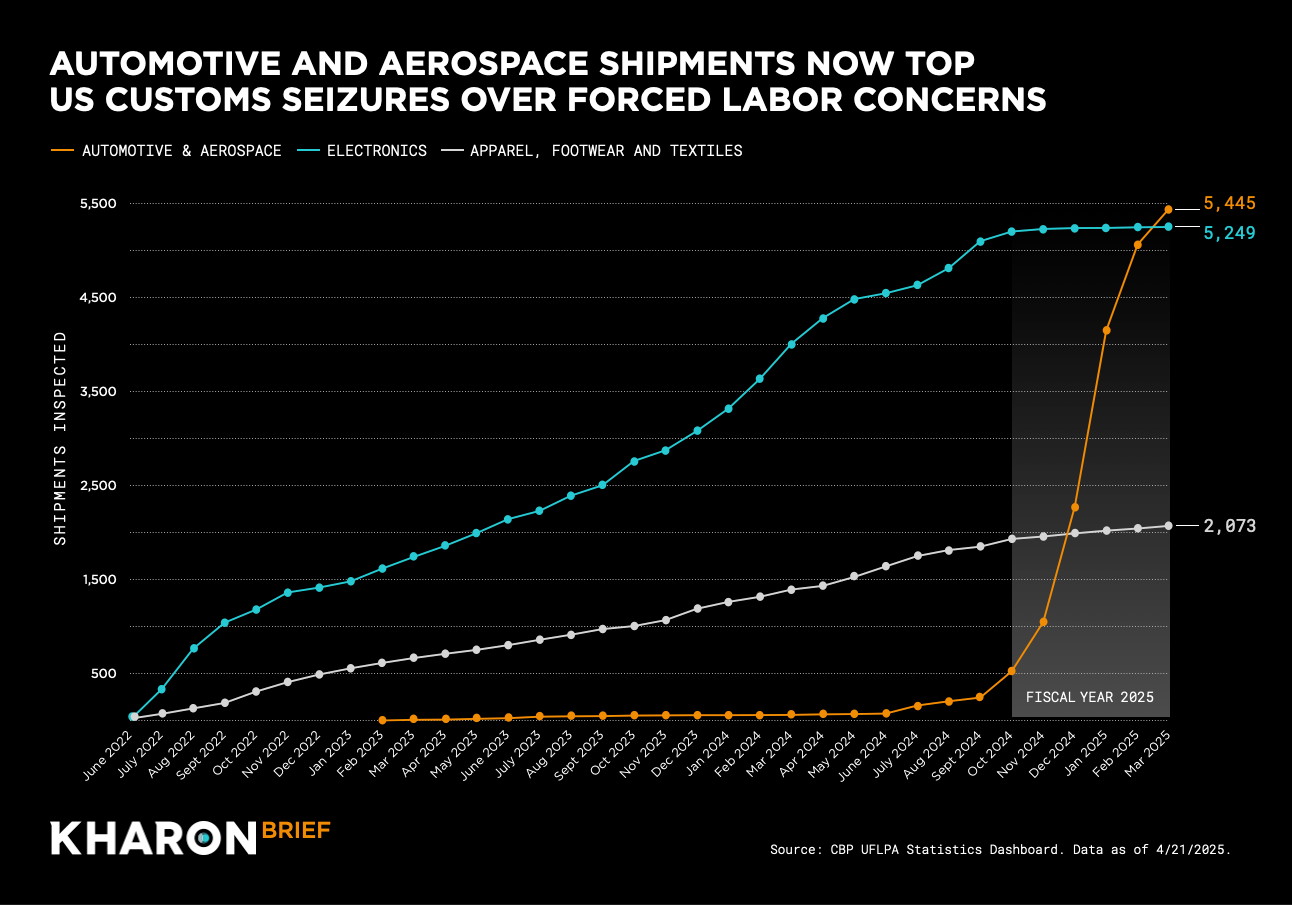

By the numbers: CBP began zeroing in on the auto and aerospace sector last fall, inspecting more shipments in the first quarter of fiscal year 2025 than in previous fiscal years in total.

Altogether, since the start of FY 2025, CBP has inspected 5,197 shipments in the auto and aerospace sector, 3,890 of which were denied entry. Just 173 were released, with the rest pending review.

It’s forcing automakers to redouble and rethink their supply chain due diligence efforts.

“You can’t wait until you’re stopped,” Matt Pohlman, the CEO of the Automotive Industry Action Group (AIAG), said in a fireside-chat webinar with Kharon Director Ethan Woolley last week. “If you wait till you’re stopped, trust me: You’re going to be in trouble.”

What to know: The UFLPA, enacted in 2022, prohibits goods produced in China’s Xinjiang region from entering the U.S. unless there is sufficient evidence that they were not made with forced labor. Companies need to rebut that presumption for their shipments to be released.

If a shipment is detained under the UFLPA, Woolley explained in the webinar, CBP does not inform the company which supplier in their chain is the source of the problem. Instead, that’s up to companies to investigate themselves—and they have limited time to make their case to get their shipment released.

By the numbers: CBP began zeroing in on the auto and aerospace sector last fall, inspecting more shipments in the first quarter of fiscal year 2025 than in previous fiscal years in total.

Altogether, since the start of FY 2025, CBP has inspected 5,197 shipments in the auto and aerospace sector, 3,890 of which were denied entry. Just 173 were released, with the rest pending review.

The latest UFLPA enforcement data, released last week, shows that 99 percent of the automotive and aerospace shipments inspected since January originated from China.

What to do: Showing that you’ve done thorough due diligence can help your case with CBP, Pohlman said. But he urged automakers to use data when interrogating their supply chains and “to find a way to be proactive, not reactive.”

“You have to take the responsibility to be aware,” Pohlman said. A detained shipment could mean “damage to your company's reputation. You could be in the headlines.”

Some businesses, Woolley said, have started with a narrower, risk-based approach, such as by scrutinizing the entire supply chain for their best-selling product and making sure that is safe first.

Another risk-based approach might involve focusing on product categories that the U.S. government explicitly prioritizes under the UFLPA or considers high-risk, such as cotton, tires, aluminum, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and lithium-ion batteries.

What to do: Showing that you’ve done thorough due diligence can help your case with CBP, Pohlman said. But he urged automakers to use data when interrogating their supply chains and “to find a way to be proactive, not reactive.”

“You have to take the responsibility to be aware,” Pohlman said. A detained shipment could mean “damage to your company's reputation. You could be in the headlines.”

Some businesses, Woolley said, have started with a narrower, risk-based approach, such as by scrutinizing the entire supply chain for their best-selling product and making sure that is safe first.

Another risk-based approach might involve focusing on product categories that the U.S. government explicitly prioritizes under the UFLPA or considers high-risk, such as cotton, tires, aluminum, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and lithium-ion batteries.

Click here to watch the full webinar on-demand.

Soundbite: “You can have eight, nine levels deep in a supply chain, and people just don’t know [what’s there], and I think the complications with this one is this is driven by the [Uyghur] Forced Labor Prevention Act,” Pohlman said. “You have to know. You have to know whether you have forced labor in your supply chain or not.”

More from Kharon on forced labor:

More from Kharon on forced labor: