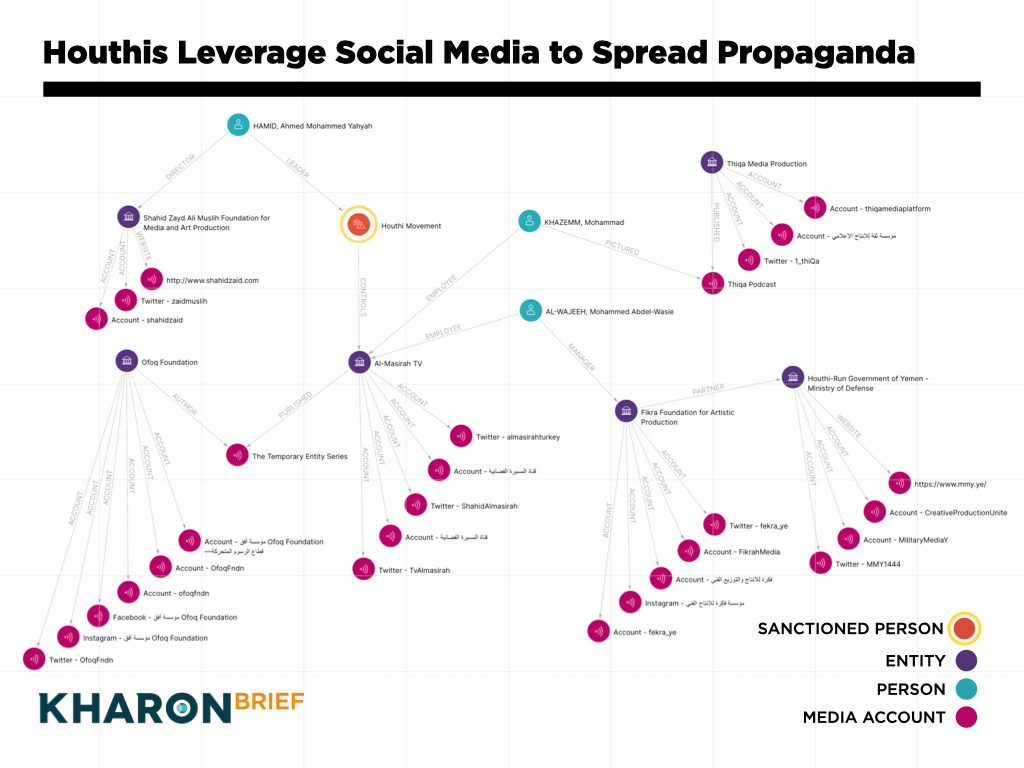

But as the Houthis’ conflict with the U.S. has escalated, Kharon has identified a network of Houthi-connected media organizations that are continuing to flood Western social media platforms with a stream of visually polished propaganda, much of it laced with hate and designed to incite violence.

Through video clips, images, written posts and children’s cartoons, the network glorifies the military might of the Houthis, who are also a main combatant in Yemen’s ongoing civil war. Much of the social media content praises the Oct. 7, 2023, attack against Israel by Hamas, which—like the Houthis—has long received Iranian support. And it frequently includes threats and depictions of attacks against Israel and the U.S.

And one byproduct of such content is that it facilitates fundraising and recruitment for the Houthis, said Blazakis, a former director of the State Department’s Counterterrorism Finance and Designations Office.

Even as, offline, the U.S. continues to confront them.

‘Social media is our weapon’

As the U.S. and the Houthis exchanged strikes in the Red Sea, a verified account posted to X an image of a ship being bombed overlaid with the words “We will defeat you” in Arabic and Hebrew. The account belonged to the Shahid Zayd Ali Muslih Foundation for Media and Art Production, one of a number of production outlets that the Houthis control.

A March 2025 X post by the Shahid Zayd Ali Muslih Foundation.

The Foundation’s content ranges. One recent video wove together footage of Houthi missile launches, war devastation in Gaza and a speech by the Houthis’ leader, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, that threatened “escalation against the Israeli enemy.” But it also features children’s characters as a vehicle for its message.

One of its publications is a children's magazine titled “The Little Ashtar,” a nickname that signifies strength, evoking a person’s fighting spirit and religious ferocity. The Shahid Zayd Ali Muslih Foundation links to the magazine’s full issues on X.

The Houthis’ apparent goal, Blazakis said, is for their social media messages to reach three audiences: their own supporters, potential “free agents” and “the enemy.” One December 2023 edition of “The Little Ashtar” makes the strategy explicit.

“Look, friends,” one of the child characters says in Arabic, “social media is our weapon with which we can provoke the Israeli enemy.”

The December 10, 2023, issue of “The Little Ashtar,” as linked to on X.

Not only do entities in the Houthis’ propaganda network share that apparent objective, but many also collaborate directly in their media production and distribution.

“The Temporary Entity,” a Houthi propaganda children’s cartoon series, is produced by a media outlet called Ofoq Foundation and airs on the Yemeni channel al-Masirah TV, which the Houthis founded and control.

Ofoq Foundation has posted the cartoon’s episodes on Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, YouTube, X, WhatsApp, TikTok and its own website. (YouTube and TikTok appear to have taken down the foundation’s channels late last month.) Al-Masirah TV has posted episodes to its main X account, which has more than 150,000 followers; it maintains another that has more than 170,000 followers, as well as several accounts on Telegram, where it has more than 180,000 subscribers.

A screengrab from an episode of “The Temporary Entity,” as promoted by Ofoq Foundation on Facebook and Instagram.

“We want to start now,” one child says. “Yes, we want to give them a harsh message,” says another.

In the finale, posted to Western platforms last month, the children help command the combined forces of the Houthis, Hamas and Hizballah to victory in an all-out war against the U.S. and Israel, striking their ships and bombing Israeli cities.

Al-Masirah TV promotes “The Temporary Entity” on X, where the channel’s main account has more than 150,000 followers and another has more than 170,000.

For context: The U.S. Treasury Department has repeatedly targeted Houthi networks since the group’s FTO re-designation in January. In March, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned top Houthi leaders for smuggling “military-grade items and weapon systems into Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen” and negotiating Houthi weapons procurement from Russia. This month, OFAC sanctioned a network involved in procuring tens of millions of dollars in Russian weapons and other goods for shipment to Yemen.

The Houthis’ social media content reveals a clear pattern: While Arabic-language content is far more inflammatory and violent, messaging in English often appears measured and political. That contrast highlights the challenge that platforms face in detecting and removing harmful content.

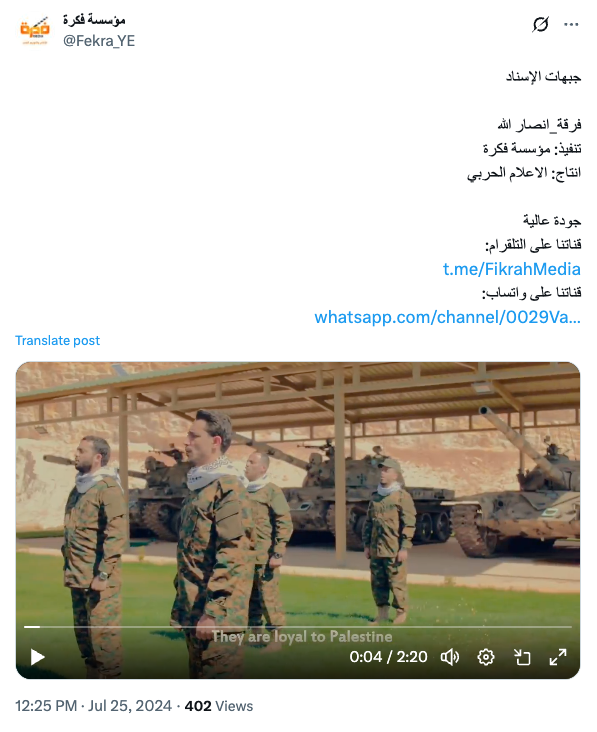

Fikra Foundation for Artistic Production, managed by an al-Masirah news anchor and producer, airs content on the channel that it later posts to X, Instagram and Threads. The posts include pictures of Houthi rallies in Yemen and English-subtitled music videos glorifying the Houthi movement. Such content is produced in partnership with Military Media—which, according to its own social media accounts’ bio, belongs to the Houthi-run Ministry of Defense.

Fikra Foundation for Artistic Production produces and posts to X English-subtitled music videos, like this one from July 2024, in partnership with Military Media.

A week before, the outlet had posted a video underscoring those threats. In it, Houthi fighters trained for combat and used a picture of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for target practice, before they lit it on fire.

Thiqa Media Production Foundation, meanwhile, does not identify itself as belonging to the Houthi movement but says it is based in Yemen. On X, YouTube and TikTok, it interviews guests such as Mohammad Khazemm, an al-Masirah TV correspondent who was wounded in Israel’s pager attack in Lebanon, and shares documentary footage in both Arabic and English that spotlights the violent history of the United States.

“All these companies have to improve their capabilities when it comes to making sure content associated with these kinds of groups—especially when violent in orientation—is removed and have experts who can speak those languages,” Blazakis said, “or at least train their potential AI tools that they're using to try to understand what kind of content might be problematic.”

YouTube has removed some of Thiqa Foundation’s full episodes for violating the platform’s Terms of Service, though the channel itself remains active, as do shorter clips on YouTube and X.

Despite being cut off from the global financial system due to U.S. and international sanctions, the Houthis continue to exploit the open nature of Western social media platforms to spread their propaganda and incite violence to wide audiences.

Social media companies face significant challenges in de-platforming these accounts and removing harmful content, especially when it reemerges in varied forms and through loosely affiliated accounts. It all complicates efforts to counter terrorism.

Read more: