At the end of last year, a Chinese chipmaking supplier some 50 miles west of Shanghai took a crucial step toward its stock market debut, by releasing the prospectus that investors would use to judge its business.

The 365-page filing detailed MaxOne Semiconductor’s revenues, its product lines and the countries from which it sourced materials to manufacture its probe cards, an obscure precision tool essential for testing advanced-computing chips before they’re packaged.

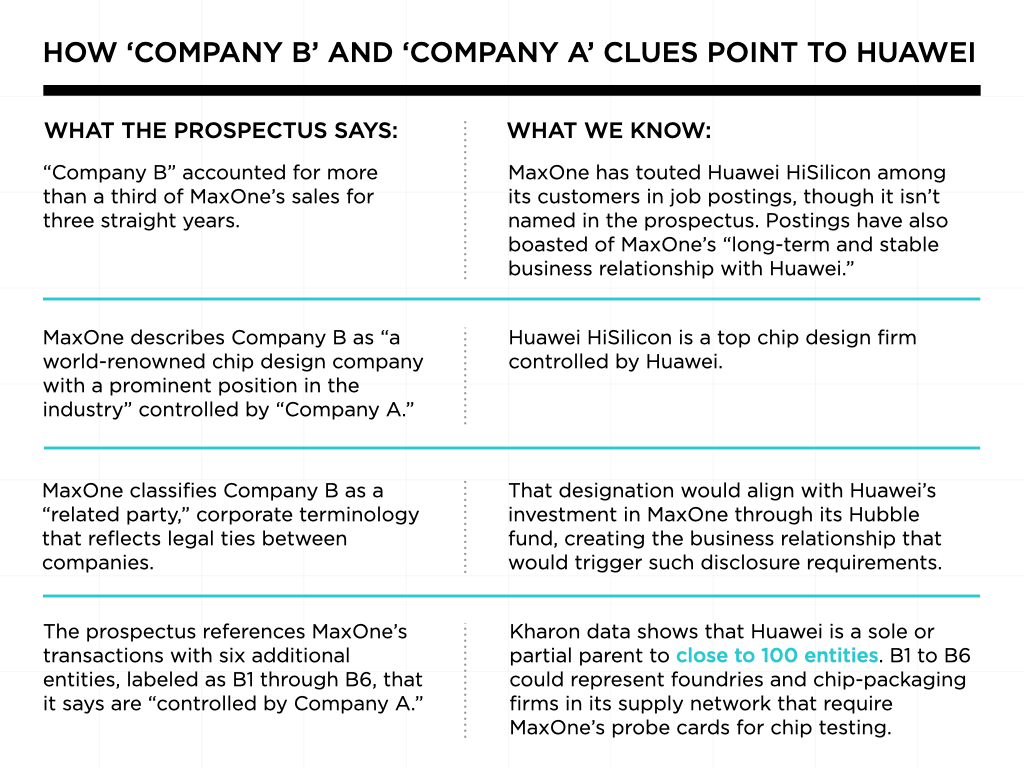

But buried in the prospectus was a curiosity. For three straight years, it said, more than a third of MaxOne’s sales had gone to one unnamed customer, “a world-renowned chip design company” it referred to only as “Company B.”

A Kharon investigation found that such customer-masking is part of a pattern among companies going public in China’s semiconductor sector, which has become a top U.S. target amid the race for artificial intelligence. Corporate filings, investment records and supply chain data suggest there may be one common partner lurking behind the anonymity: the Chinese tech giant Huawei, which the U.S. has targeted with criminal indictments, equipment bans and sweeping export restrictions for years.

The 365-page filing detailed MaxOne Semiconductor’s revenues, its product lines and the countries from which it sourced materials to manufacture its probe cards, an obscure precision tool essential for testing advanced-computing chips before they’re packaged.

But buried in the prospectus was a curiosity. For three straight years, it said, more than a third of MaxOne’s sales had gone to one unnamed customer, “a world-renowned chip design company” it referred to only as “Company B.”

A Kharon investigation found that such customer-masking is part of a pattern among companies going public in China’s semiconductor sector, which has become a top U.S. target amid the race for artificial intelligence. Corporate filings, investment records and supply chain data suggest there may be one common partner lurking behind the anonymity: the Chinese tech giant Huawei, which the U.S. has targeted with criminal indictments, equipment bans and sweeping export restrictions for years.

After U.S. restrictions hit in 2019, Huawei activated what it called a “spare tire” plan to build a sanctions-proof supply chain. Partnerships with the semiconductor firms—a few of which, like MaxOne, source from the U.S.—appear to show that strategy in action, experts said.

“Huawei has long tried to build as much of an end-to-end supply chain as possible, relying where possible on domestic suppliers or affiliated firms,” said Chris Miller, a professor at Tufts University and author of “Chip War,” a history of the semiconductor industry. Huawei, Miller said, “has the market position to fund startups and serve as their primary customer. When it comes to chip companies in China, affiliation with Huawei is a significant advantage.”

But when going public, experts say, several factors could be at play: Companies that reveal deep Huawei ties could risk attracting U.S. sanctions, a risk that could also scare off investors, or they could be trying to shield Huawei by obscuring its suppliers at the government’s direction.

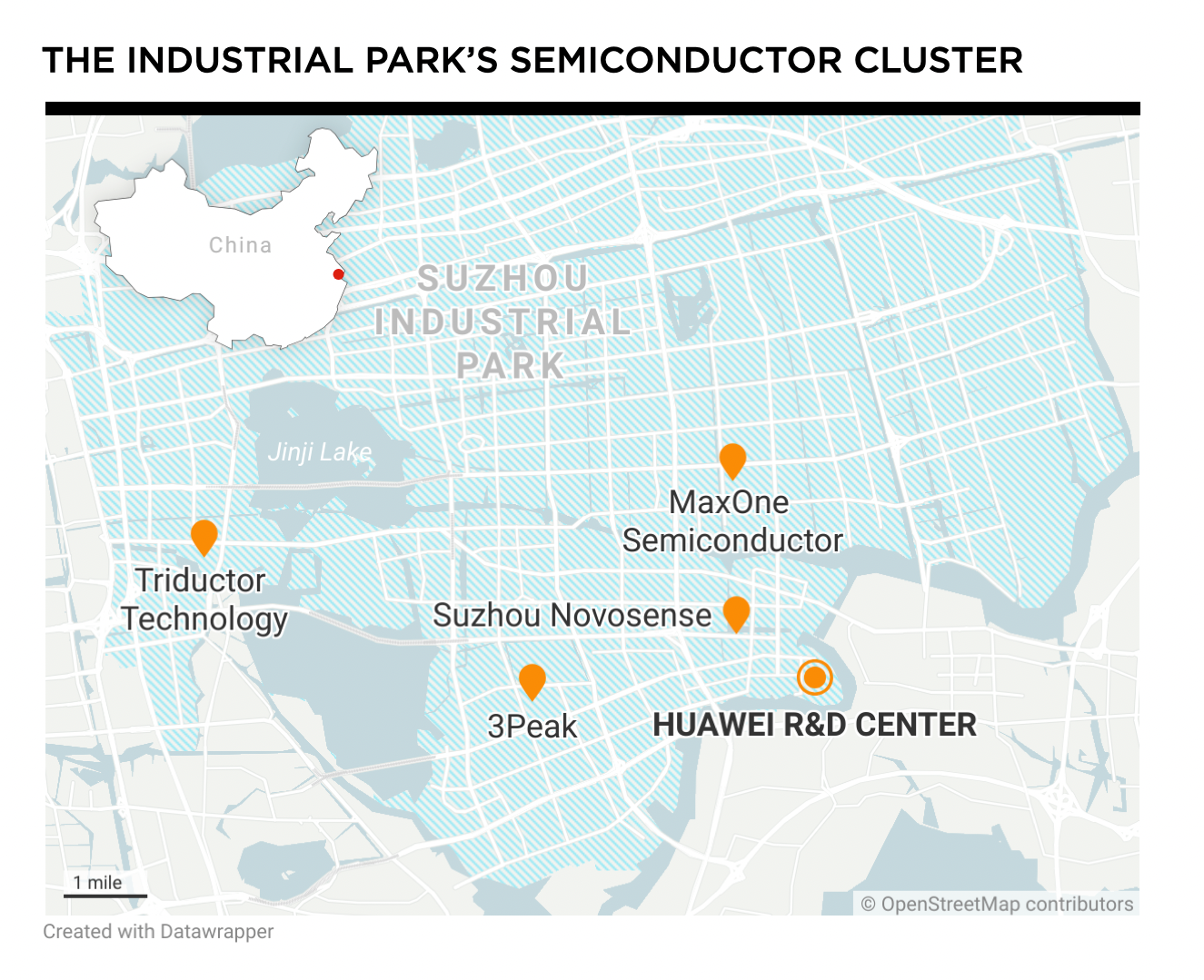

Kharon’s findings signal the extent to which Huawei’s drive for an independent supply chain has advanced, partly out of sight. Much of it appears to be unfolding in the same multibillion-dollar ecosystem, the industrial park where MaxOne has taken off.

“Huawei has long tried to build as much of an end-to-end supply chain as possible, relying where possible on domestic suppliers or affiliated firms,” said Chris Miller, a professor at Tufts University and author of “Chip War,” a history of the semiconductor industry. Huawei, Miller said, “has the market position to fund startups and serve as their primary customer. When it comes to chip companies in China, affiliation with Huawei is a significant advantage.”

But when going public, experts say, several factors could be at play: Companies that reveal deep Huawei ties could risk attracting U.S. sanctions, a risk that could also scare off investors, or they could be trying to shield Huawei by obscuring its suppliers at the government’s direction.

Kharon’s findings signal the extent to which Huawei’s drive for an independent supply chain has advanced, partly out of sight. Much of it appears to be unfolding in the same multibillion-dollar ecosystem, the industrial park where MaxOne has taken off.

The Case of ‘Company B’

Suzhou Industrial Park. (Adobe Stock Images)

The nearly 70,000-acre Suzhou Industrial Park emerged in the 1990s from land that formerly belonged to rice paddies. MaxOne launched there in 2015, joining a burgeoning semiconductor ecosystem.

In 2021, MaxOne received an investment from Hubble Technology, one of Huawei’s most active and visible venture-capital arms. The following year, a senior Huawei employee who had overseen global procurement joined MaxOne’s board, and it launched its exploration process for a Shanghai IPO. The company is now aiming to raise $210 million.

In its prospectus, MaxOne presents itself as China’s premier probe-card manufacturer at a time of “persistent uncertainty in the international situation.” Its mission, it says, is “to serve national strategy and ensure supply security for China’s semiconductor products.”

In 2021, MaxOne received an investment from Hubble Technology, one of Huawei’s most active and visible venture-capital arms. The following year, a senior Huawei employee who had overseen global procurement joined MaxOne’s board, and it launched its exploration process for a Shanghai IPO. The company is now aiming to raise $210 million.

In its prospectus, MaxOne presents itself as China’s premier probe-card manufacturer at a time of “persistent uncertainty in the international situation.” Its mission, it says, is “to serve national strategy and ensure supply security for China’s semiconductor products.”

President Xi Jinping, at left, visits Suzhou Industrial Park in July 2023, highlighting China’s push for tech self-reliance. (CCTV footage)

They’re closely related ideas. When Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Suzhou Industrial Park in 2023, hailing it as a “City of Innovation,” he declared that achieving “technological self-reliance” had become essential to China’s future as a global power. In the years prior, the U.S. successively had indicted Huawei for allegedly stealing U.S. companies’ trade secrets; named it and 46 of its affiliates to the Entity List, constricting their access to American components; and labeled Huawei as a Chinese military company.

The spare-tire plan arose against that backdrop. And the records reviewed by Kharon suggest that MaxOne’s unnamed Company B is HiSilicon, Huawei’s prominent semiconductor design arm.

The spare-tire plan arose against that backdrop. And the records reviewed by Kharon suggest that MaxOne’s unnamed Company B is HiSilicon, Huawei’s prominent semiconductor design arm.

MaxOne did not respond to emailed questions about its relationships with Huawei and HiSilicon, the identity of its top customer, or whether any of the U.S. components it imports ultimately flow to Huawei. Huawei and HiSilicon also did not respond.

But past MaxOne job postings, reviewed by Kharon, explicitly promoted the firm’s Huawei connections to attract talent.

“Declining transparency is a broad trend across strategic industries in China,” said Jacob Feldgoise, an analyst who studies semiconductor supply chains at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology. Regarding semiconductor supply chains, he said, “the most obvious reason is Huawei—no partner wants to risk being Entity Listed by the U.S. But it’s not entirely due to export controls. It also comes from worsening U.S.-China relations and perhaps some amount of mandate from state agencies to hide certain pieces of information.”

MaxOne’s prospectus did disclose its second- and third-largest customers of 2024, both of which are on the U.S. Entity List and have their own documented ties to Huawei:

But past MaxOne job postings, reviewed by Kharon, explicitly promoted the firm’s Huawei connections to attract talent.

- “Our products have been successfully adopted by well-known domestic and international companies, including Huawei HiSilicon,” one posting read.

- “The company has established a long-term and stable business relationship with Huawei,” read another.

“Declining transparency is a broad trend across strategic industries in China,” said Jacob Feldgoise, an analyst who studies semiconductor supply chains at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology. Regarding semiconductor supply chains, he said, “the most obvious reason is Huawei—no partner wants to risk being Entity Listed by the U.S. But it’s not entirely due to export controls. It also comes from worsening U.S.-China relations and perhaps some amount of mandate from state agencies to hide certain pieces of information.”

MaxOne’s prospectus did disclose its second- and third-largest customers of 2024, both of which are on the U.S. Entity List and have their own documented ties to Huawei:

- Shenghejing Micro, which accounts for 22 percent of MaxOne’s sales, is a foundry that partners with Huawei on its AI Ascend chips.

- Quliang Electronics (14 percent of MaxOne’s sales) was specifically added to the Entity List for activities supporting Huawei.

At the same time, MaxOne says it sources from U.S., South Korean, and Japanese suppliers. That raises the possibility that their components could ultimately flow through MaxOne to a company that U.S. restrictions are designed to isolate.

Huawei’s ‘Rocket Engine’ Effect

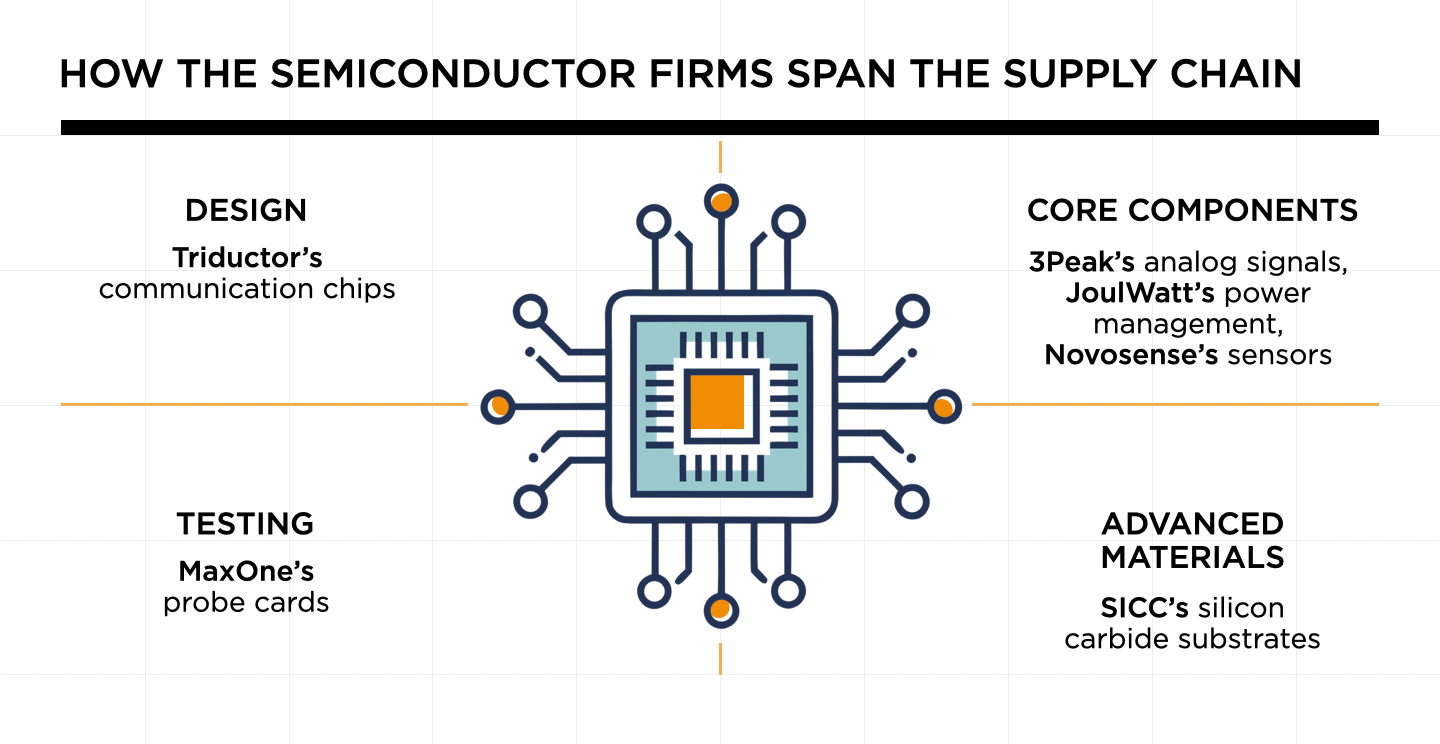

But MaxOne is just one link in the chain. Kharon identified six Chinese manufacturers of semiconductor components that in recent years have followed the same distinct pattern:- receive investment from Huawei directly or through one of its funds.

- strengthen ties to Huawei through sales, public partnerships and/or the addition of Huawei executives to their boards.

- pursue an IPO on the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

- anonymize their biggest client in their prospectuses.

“These relatively unknown ‘startups’ are more able than China’s well-known tech giants, like Huawei, to avoid the scrutiny of foreign governments, gain access to Taiwanese or Western technology and services, and ultimately integrate those into China’s broader national semiconductor strategy,” said Jeremy Chang, CEO of the Research Institute for Democracy, Society, and Emerging Technology (DSET), a Taiwanese think tank.

Huawei’s then-newly formed Hubble fund offered an avenue for protest when U.S. export controls kicked in, Chang said. “It’s almost like propaganda, telling Chinese patriots: We’re sanctioned by the Americans, so we’re setting up a fund to support our tech frontier.”

One of Hubble’s earliest investments, in May 2019, was in the analog chip maker 3Peak, located just a few blocks from MaxOne. Two months later, Huawei opened its New Suzhou AI R&D base in the industrial park; a news release said it was designed to serve as a hub for “supply chain integration.” Nearby semiconductor firms soon began ramping up with IPOs.

Huawei’s then-newly formed Hubble fund offered an avenue for protest when U.S. export controls kicked in, Chang said. “It’s almost like propaganda, telling Chinese patriots: We’re sanctioned by the Americans, so we’re setting up a fund to support our tech frontier.”

One of Hubble’s earliest investments, in May 2019, was in the analog chip maker 3Peak, located just a few blocks from MaxOne. Two months later, Huawei opened its New Suzhou AI R&D base in the industrial park; a news release said it was designed to serve as a hub for “supply chain integration.” Nearby semiconductor firms soon began ramping up with IPOs.

3Peak became the first company in the Hubble portfolio to reach the Shanghai Stock Exchange, in September 2020. Its IPO filing stated that a “related party” it called “Client A” had transformed it from a struggling startup into a profitable enterprise in just over a year.

Client A, the prospectus said, was a “domestic information and communication infrastructure provider” that had become 3Peak’s largest client in 2019, the year Hubble had invested. Among 3Peak’s “risks,” it listed recent U.S. measures targeting Chinese communications companies that it said could create “adverse or potentially adverse impacts” on Client A. Among the named measures were “entity lists” and the “Clean Network initiative,” both of which had targeted Huawei.

Chinese media celebrated 3Peak’s meteoric rise right up through June 2021, when it became Shanghai’s highest-valued semiconductor company. “Getting Huawei’s support is like installing a rocket engine instant takeoff,” wrote Jiemian News, a financial and business news outlet.

It marked a major successful test case. Others soon followed.

Client A, the prospectus said, was a “domestic information and communication infrastructure provider” that had become 3Peak’s largest client in 2019, the year Hubble had invested. Among 3Peak’s “risks,” it listed recent U.S. measures targeting Chinese communications companies that it said could create “adverse or potentially adverse impacts” on Client A. Among the named measures were “entity lists” and the “Clean Network initiative,” both of which had targeted Huawei.

Chinese media celebrated 3Peak’s meteoric rise right up through June 2021, when it became Shanghai’s highest-valued semiconductor company. “Getting Huawei’s support is like installing a rocket engine instant takeoff,” wrote Jiemian News, a financial and business news outlet.

It marked a major successful test case. Others soon followed.

- Suzhou Novosense Microelectronics completed its own Shanghai listing later in 2022, two years after Huawei indirectly invested in it. Chinese tech media had dubbed the sensor maker “the next 3Peak,” and its IPO filing deepened the comparison: It shared that an unnamed “Client A,” which it described as a “domestic first-tier” manufacturer of information and communication technology, had dominated the company’s business from 2019 to 2020.

- Two other companies in Hubble’s portfolio also went public that year: SICC, a silicon carbide substrate maker based in Shandong, and JoulWatt Technology, a power-management chip designer from Hangzhou. Both companies’ filings again featured anonymous “related parties” as anchor customers; a Huawei enterprise development executive sits on both firms’ boards.

Hidden Ties, Visible U.S. Exposure

Founders and major shareholders of several of the companies Kharon identified are U.S. citizens, including the founder of the last of the six: the communication chip designer Triductor Technology. It’s the firm that, even more so than MaxOne, most directly illustrates the anonymization pattern’s potential risks to U.S. tech.“These relatively unknown ‘startups’ are more able than China’s well-known tech giants, like Huawei, to avoid the scrutiny of foreign governments, gain access to Taiwanese or Western technology and services, and ultimately integrate those into China’s broader national semiconductor strategy.”

- Jeremy Chang, CEO of Taiwan’s DSET think tank

Triductor, located across the industrial park’s lake from MaxOne and 3Peak, went public in Shanghai in 2022. Its prospectus disclosed that it uses U.S.-licensed software and intellectual property for chip design while also serving at least two Entity Listed customers, presenting a risk that Triductor’s U.S. tech could be diverted.

But the prospectus also withheld the identity of a “Company A,” responsible for 53% of its sales, which it described as a “global leading telecom infrastructure provider.”

And Huawei, whose name did not appear in Triductor’s client list, has a web of close ties to Triductor past and present.

The U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security, he said, “is essentially playing whack-a-mole, struggling to keep up with the speed of new company formations and tactics used to circumvent export controls.”

But the semiconductor network also reflects China’s broader strategy gaining momentum, experts said. After the construction of self-reliant supply chains comes the next major goal: developing technology that can challenge Western superiority.

Hubble is only the “visible layer” of Huawei’s sanctions-evasion strategy, Chang said, and the invisible ones are set up to skirt U.S. controls. “There are at least thousands of such companies,” he said. “Many don’t even have websites. You have to dig very deep to find clues.”

According to Chinese state media, Huawei chief executive Ren Zhengfei met with Xi in February and described a plan to lead a network of more than 2,000 companies working toward 70% semiconductor self-sufficiency by 2028. Ren called the plan “Spare Tire 2.0.”

Miller, the “Chip War” author, said its goal was “broadly realistic.”

“China is making rapid strides at reaching self-sufficiency in everything except for the most advanced chipmaking tools and materials,” he said. “For less advanced semiconductors, China’s domestic capabilities are progressing rapidly.”

For that progress, at least in part, it can credit Companies A and B.

More from the Kharon Brief:

But the prospectus also withheld the identity of a “Company A,” responsible for 53% of its sales, which it described as a “global leading telecom infrastructure provider.”

And Huawei, whose name did not appear in Triductor’s client list, has a web of close ties to Triductor past and present.

- According to records reviewed by Kharon, Huawei invested in Triductor until 2017 via Hua Ying Management Co. Limited. The U.S. later named Hua Ying Management to the Entity List for its “significant risks” to national security; the Commerce Department said there was “reasonable cause to believe that Huawei would seek to use [it] to evade the restrictions imposed by its addition to the Entity List.”

- Triductor recruitment posts for years advertised positions on a team that it established in 2012 “to serve Huawei’s [integrated circuit] design unit,” with “staff based in several of Huawei’s research institutes.” A 2017 posting described the team as “responsible for the design implementation of Huawei HiSilicon’s analog-digital chips.” A posting from 2021, this one now withholding the partner’s name, said that “around 300 team members are currently embedded in a leading domestic IC design company.”

- Triductor frequently mentioned Huawei as a partner and a user of its products in press releases and social media posts prior to 2020, a Kharon review found. The company has since removed some online references to its relationship with Huawei.

The U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security, he said, “is essentially playing whack-a-mole, struggling to keep up with the speed of new company formations and tactics used to circumvent export controls.”

From Self-Reliance to Superiority

Huawei’s U.S. federal court case is finally set for trial in 2026, more than seven years after its indictment. By then, MaxOne may well have completed its IPO and joined the five other semiconductor firms listed in Shanghai—where they’re now worth $16 billion combined, providing fresh capital for expansion and continued foreign tech acquisition.But the semiconductor network also reflects China’s broader strategy gaining momentum, experts said. After the construction of self-reliant supply chains comes the next major goal: developing technology that can challenge Western superiority.

Hubble is only the “visible layer” of Huawei’s sanctions-evasion strategy, Chang said, and the invisible ones are set up to skirt U.S. controls. “There are at least thousands of such companies,” he said. “Many don’t even have websites. You have to dig very deep to find clues.”

According to Chinese state media, Huawei chief executive Ren Zhengfei met with Xi in February and described a plan to lead a network of more than 2,000 companies working toward 70% semiconductor self-sufficiency by 2028. Ren called the plan “Spare Tire 2.0.”

Miller, the “Chip War” author, said its goal was “broadly realistic.”

“China is making rapid strides at reaching self-sufficiency in everything except for the most advanced chipmaking tools and materials,” he said. “For less advanced semiconductors, China’s domestic capabilities are progressing rapidly.”

For that progress, at least in part, it can credit Companies A and B.

More from the Kharon Brief: