Sanctions have cut off Iran’s major banks from the global financial system. That’s led the Iranian government to rely heavily on “shadow” banking networks to evade sanctions and move money—particularly from oil and petrochemical sales—across borders. The funds involved can be substantial.

In June, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned multiple members of Iran’s Zarringhalam family and their businesses for operating a shadow-banking scheme that it said had “collectively laundered billions of dollars through the international financial system” on behalf of Iranian government-controlled entities. Brothers Mansour, Nasser and Fazlolah Zarringhalam were at the center of it.

Kharon’s research found that the Zarringhalams’ broader family tree is deeply rooted in Iran’s currency trading community, which connects Iranian importers and exporters with foreign currencies that local banks can’t access. And that tree’s active branches extend past what Treasury captured.

How it works: A typical shadow banking network begins with an Iran-based private currency trading company and extends to numerous front companies that it controls abroad. The Zarringhalam exchange houses, Treasury said, leveraged front companies primarily in Hong Kong and the United Arab Emirates “to make or receive payments on behalf of sanctioned persons in Iran.”

According to Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), red flags for shadow banking activity include:

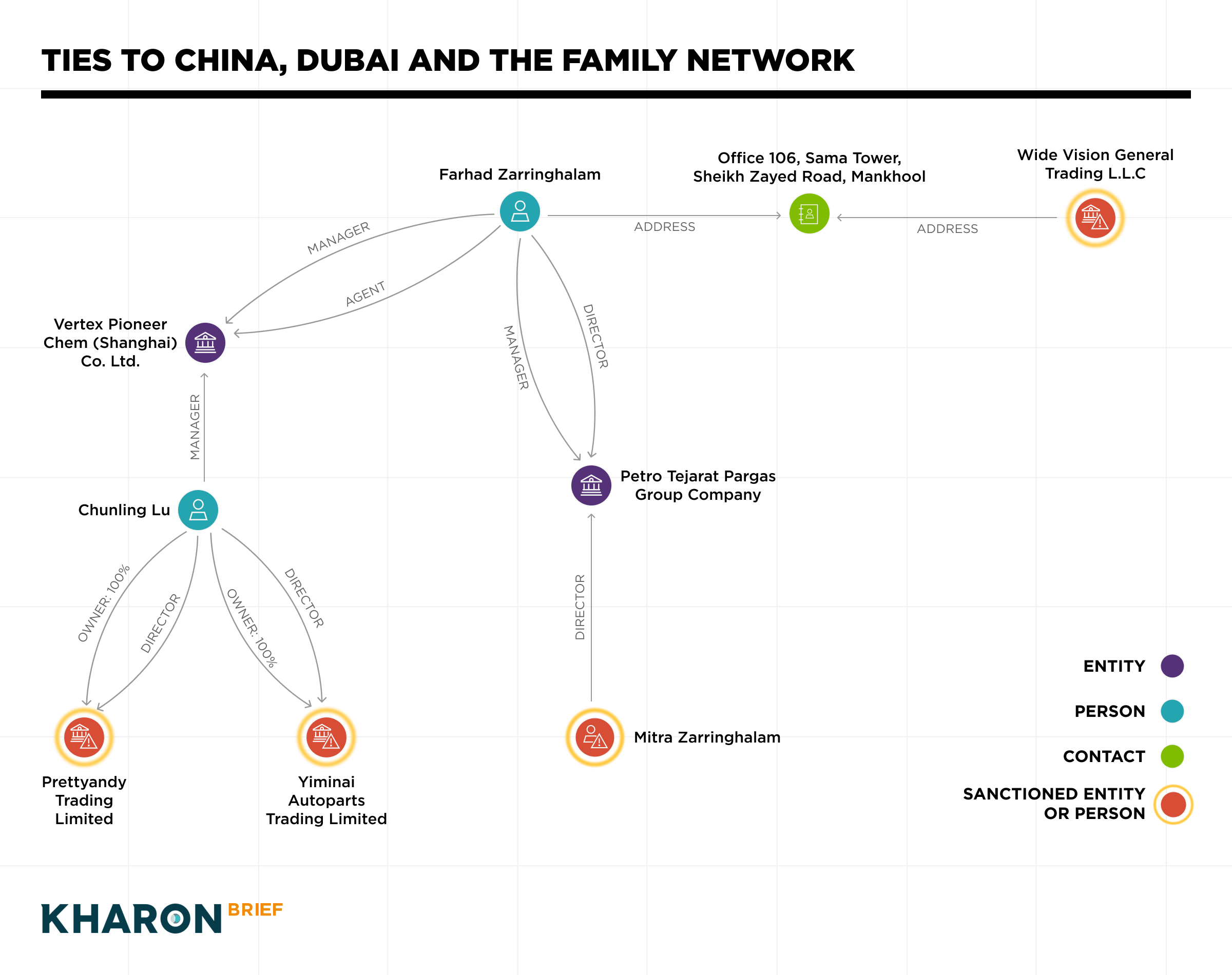

Family ties: One such relative is Farhad Zarringhalam, who has U.K. citizenship. He manages one company in Singapore and another in the UAE, both of which specialize in oil, gas and petrochemical trading. But his other past and present associations are many:

In June, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned multiple members of Iran’s Zarringhalam family and their businesses for operating a shadow-banking scheme that it said had “collectively laundered billions of dollars through the international financial system” on behalf of Iranian government-controlled entities. Brothers Mansour, Nasser and Fazlolah Zarringhalam were at the center of it.

Kharon’s research found that the Zarringhalams’ broader family tree is deeply rooted in Iran’s currency trading community, which connects Iranian importers and exporters with foreign currencies that local banks can’t access. And that tree’s active branches extend past what Treasury captured.

How it works: A typical shadow banking network begins with an Iran-based private currency trading company and extends to numerous front companies that it controls abroad. The Zarringhalam exchange houses, Treasury said, leveraged front companies primarily in Hong Kong and the United Arab Emirates “to make or receive payments on behalf of sanctioned persons in Iran.”

According to Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), red flags for shadow banking activity include:

- A customer who makes transactions that “move through multiple exchange houses and/or trading companies, adding additional fees and costs as the transactions progress,” in a pattern that does not reflect “standard and customary commercial practices.”

- An exchange house or trading company in a jurisdiction near Iran that “uses forged or falsified documents to conceal the identity of parties involved in transactions that will utilize regional banks’ correspondent banking relationships with U.S. financial institutions to access U.S. dollars.”

- A general trading company that has bank accounts at multiple UAE financial institutions, is “registered in a commercial free trade zone in the UAE with opaque ownership,” and whose counterparties are companies mostly located in Hong Kong and/or Singapore.

Family ties: One such relative is Farhad Zarringhalam, who has U.K. citizenship. He manages one company in Singapore and another in the UAE, both of which specialize in oil, gas and petrochemical trading. But his other past and present associations are many:

- According to the Official Gazette of Iran, Farhad is managing director of a Tehran-based petroleum company, Petro Tejarat Pargas Group Company, alongside the sanctioned Mitra Zarringhalam.

- In U.K. corporate registration documents filed in 2015, Farhad listed his address as 106 Sama Tower in Dubai. A third-party business database lists that as an address for Wide Vision General Trading, a Zarringhalam-controlled company sanctioned in June for coordinating shadow-banking transactions. The sanctioned Mansour Zarringhalam used the same address to register a company in Panama in 2013.

- As of 2022, Farhad also was executive director of a Shanghai-based chemical company, Vertex Pioneer Chem. That firm’s listed liquidation manager, Lu Chunling, is the sole owner of two Hong Kong companies that were both designated for being part of the Zarringhalam shadow-banking network.

Kharon users can explore this Insight in greater detail through the ClearView platform.

Another family member Kharon identified is Sina Zarringhalam, who according to a social media account is a sibling of the sanctioned Pouria Zarringhalam.

Even more consequential moves may be in store: Last week, France, Germany and the U.K. told the UN that they were “prepared” to restore broad sanctions on Iran if the country does not demonstrate that it’s “willing to reach a diplomatic solution” on limiting its nuclear program.

More from the Kharon Brief:

- Sina claims to be based in Switzerland, but he manages two Dubai-based companies purportedly involved in trading commodities: Levanterra FZCO and Levanterra Co L.L.C. The Leventerra website indicates that it shares the same address that OFAC listed for Wide Vision.

- Kaj Exchange is co-owned by Behzad Zarringhalam, Feizollah Zarringhalam and Hamed Afzali. Behzad Zarringhalam’s Facebook account shows that he is friends with both Sina and Pouria Zarringhalam.

- Risk factor: Unlike a bank that wires money into an account, exchange houses can leave little paper trail. In designating the Zarringhalams’ other exchange houses, Treasury warned: “To justify payments for sanctioned goods, shadow banking brokers may generate fictitious invoices or transaction details.”

Even more consequential moves may be in store: Last week, France, Germany and the U.K. told the UN that they were “prepared” to restore broad sanctions on Iran if the country does not demonstrate that it’s “willing to reach a diplomatic solution” on limiting its nuclear program.

More from the Kharon Brief:

- Mapping the Iran ‘Shipping Empire’ the US Hit with a Massive Wave of Sanctions

- By the Numbers: US ‘Maximum Pressure’ Reaches Far Beyond Iran’s Borders

- Two Iranian Shadow Fleet Firms Were Sanctioned. Their Directors Have a History.

- Navigating Risk in a Reopening Syria, Where Most (But Not All) Western Sanctions Are Gone