When the European Union and United Kingdom instituted their wartime restrictions on shipping Russian oil and oil products, commodities brokers suggested they had cut such trade off.

But not all had.

One London-based company, Giran Alliance, had listed a number of Russian “partners” on its website, including the now-sanctioned oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil, before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. After the invasion, Giran Alliance updated its site and deleted those references—even though trade records show that it continued to import from Russian firms into at least early 2024.

A host of other brokers also kept dealing in Russian oil and oil products after the EU’s and U.K.’s maritime embargoes took hold, a Kharon investigation found, underscoring the West’s challenges in curbing Russia’s oil revenues well into its war in Ukraine. Some brokers brought in Russian shipments worth billions of dollars, with hundreds of them marked for entry into Europe even as officials moved to curtail precisely that kind of trade.

Kimberly Donovan, director of the Economic Statecraft Initiative at the Atlantic Council, said in an interview that such open Russian trading suggests a broader range of participants was likely involved.

“If this was findable, what’s going on that’s actually that much more difficult to identify?” Donovan said.

Western leaders in recent months have targeted Russia’s oil trade more directly than ever before, first by reinforcing the international price cap on Russian oil and then by imposing sanctions against its top producers and their subsidiaries. The EU’s latest sanctions package also designated further companies in China and elsewhere for buying Russian oil.

But Kharon’s review of trade documents, corporate records and archived corporate websites shows how the lucrative Russian oil trade persisted in Europe, too, despite what some brokers moved to signal publicly.

The Oil Price Cap and Embargoes, Explained

The details: The G7, EU and Australia implemented a price cap on Russian oil in December 2022. It set an initial ceiling of $60 USD per barrel for Russian crude and, later, separate limits for refined products like diesel.

The framework still allows Western companies to provide shipping, insurance and other services to move Russian oil to third countries if it’s sold at or below the cap.

The EU and U.K. also placed embargoes that same month on the shipping of Russian oil into the EU and U.K. themselves. The EU expanded its maritime embargo to cover oil products two months later, in February 2023.

The objectives:

1. Squeeze Moscow’s oil revenues, to hamper its warfighting abilities in Ukraine.

2. Allow Russian oil to keep flowing legally into global markets, to avoid supply chain shocks and price spikes.

Pre-invasion partners, post-invasion edits

Both the EU’s and U.K.’s embargoes landed with narrow “carve-outs,” noted James Neale, a London-based senior associate at the global law firm HFW who specializes in sanctions, customs and export controls. The existence of the price cap on Russian oil, Neale said, acknowledges that it would need to continue to flow lawfully, albeit under restrictions and threat of sanctions for violations.The Yadran Group, a Russian conglomerate, was hit with EU sanctions last month for its involvement in the country’s oil sector. After its designation, Kharon research uncovered an affiliated Swiss oil trader, Ipek SA, that trade records say imported Russian oil products marked for Europe after the invasion and around the time of the embargo.

Ipek SA shares its name with Irek (Ирек) Salikhov, the wealthy Russian politician who controls Yadran Group and whose father, according to corporate records, is a manager of Ipek SA.

But clients would not have been able to discern the Russian origin of Ipek oil products from its website.

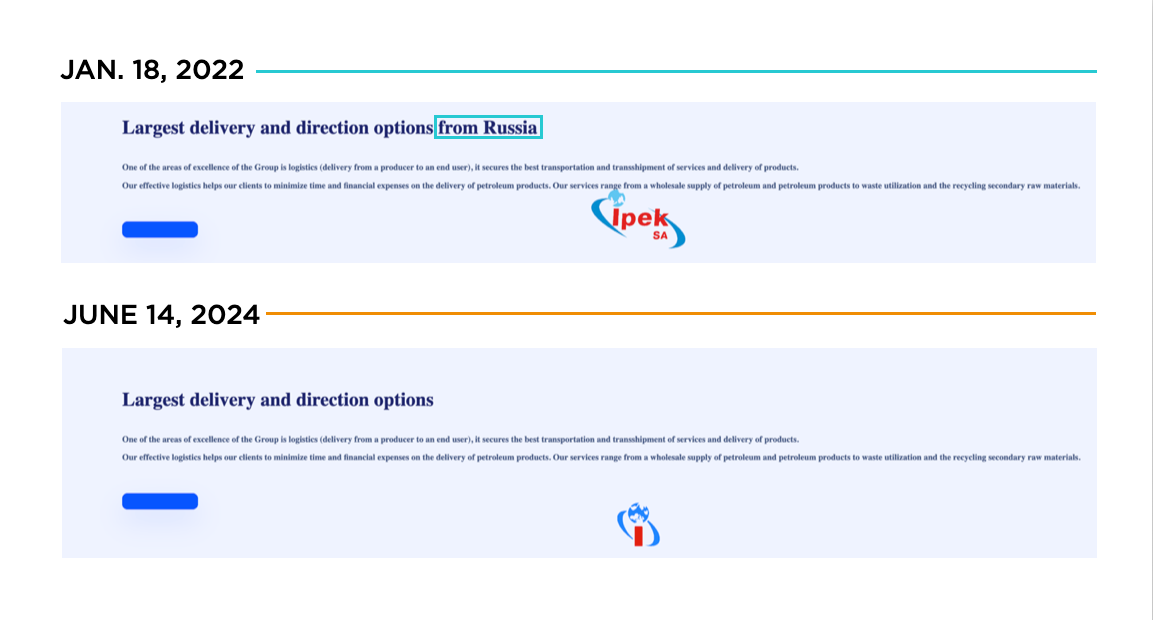

According to archived versions of its site, Ipek advertised both the logos of Russian oil companies and “delivery and direction options from Russia” until sometime before August 2022, at which point all its partners’ logos and the phrase “from Russia” were deleted. After those changes, however, available bills of lading reviewed by Kharon show the Swiss company continuing to import oil products exclusively of Russian origin.

“Ipek SA is not engaged in any business activities with Russia, nor do we have any involvement with Russian oil products or other goods with a Russian nexus,” a spokesperson wrote.

A Kharon review of Russian trademarks found that Irek Salikhov was registered as the owner of the Ipek trademark that serves as Ipek SA’s primary logo online. The company’s site continued to tout its extensive European customer base, specifically citing Spain, Italy and the Netherlands.

Europe’s trade in Russian oil has “declined severely, but it’s still very much active,” Donovan said. An August piece that she published for the Atlantic Council recorded that India and China had bought the most Russian oil in the second quarter of 2025, followed by Italy and Turkey (38 million barrels apiece) and the Netherlands (21 million).

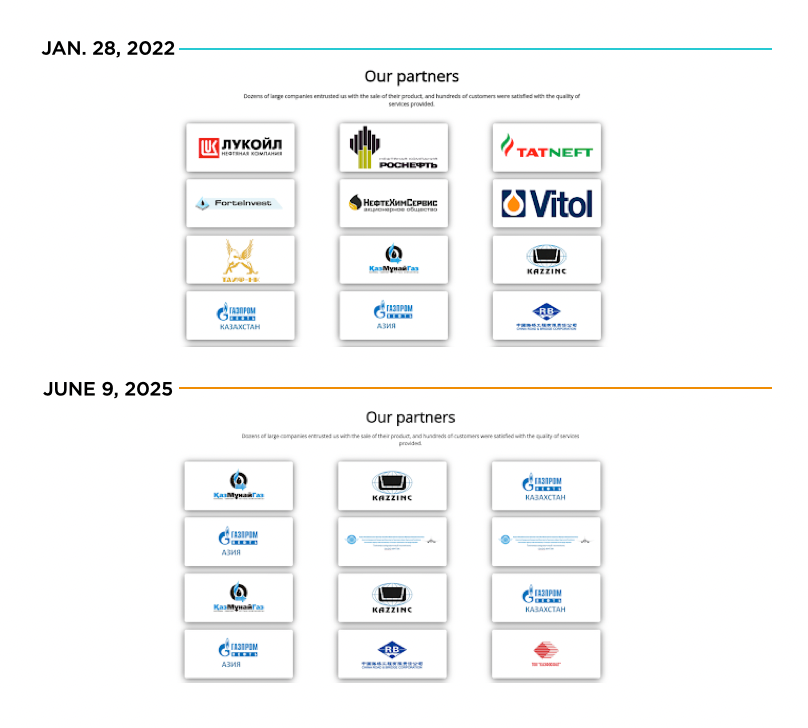

Separately, Giran Alliance, the London-based trader, dropped from its website after the invasion mentions of Rosneft, Lukoil, Tatneft and other Russia-based firms from its list of featured “partners.” (Gazprom’s Central Asian subsidiaries remained.)

But trade records show that Giran Alliance continued to import Russian oil and oil products until at least March 2024, including from some of those same deleted companies.

Before the invasion, Giran Alliance’s listed “partners” included Lukoil, Rosneft, Tatneft and Forteinvest. Sometime after, all the Russia-based partners disappeared, though Gazprom’s Central Asian subsidiaries remained. (Screenshot via Internet Archive)

- shipments of oil and crude oil products from Rosneft and its subsidiary RN-Trans, some of those bound for the U.K.;

- shipments of petroleum products from Moscow-based Oyl Tekhnolodzhis OOO, several again bound for the U.K.;

- and shipments of gasoline from Tatneft and Forteinvest, two Russian companies that Giran Alliance formerly listed as partners, with some of Forteinvest’s marked for the U.K. and Malta.

Malta, the EU’s smallest country by size and economy, surfaced repeatedly in trade records as a destination for Russian oil products. Its Customs Department also did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

Operating abroad, importing to Europe

Brokers based in third countries like Hong Kong, the UAE and Singapore have become key intermediaries of the Russian oil trade since the invasion. Some of them, like Hong Kong-based Gigaflex Asia Limited, had signaled their supposed exits from Russia in subtle ways.Gigaflex Asia director Rustem Kadyrov, a Swedish national, has a history with illicit oil dating to the 1990s, when Latvia’s prosecutor general alleged that he had smuggled thousands of tons of it into the country. Alongside fellow Swede Lyudmila Kadyrova, he now runs Gigaflex Asia, which trade records show received dozens of shipments of oil products from Russian companies into at least April 2024, including post-embargo shipments marked for Greece, the Netherlands and Malta.

Gigaflex Asia prominently promoted “executed and current projects in Russia” on its website’s homepage before the 2022 invasion, according to an archived version of the site. But sometime after, it edited that sentence to delete Russia and swap in Georgia instead:

Even if a company isn’t violating any laws, Donovan said, “they just may be choosing not to publicize that they’re continuing to do this because they don't want to scare off customers or trading partners.” An oil broker might see particular value, she said, in concealing their Russian business from Western banks, which have been “the tip of the spear” in implementing sanctions.

Dubai-based AP International Petroleum Trading DMCC is among the intermediaries whose profits from Russian oil have jumped since the war began. A Wall Street Journal report listed it as one of 2023’s top 10 exporters of Russian refined oil products; according to financial statements, AP International bought more than $1 billion worth of products from one Russian oil company alone, Slavyansk Eco LLC, in both 2023 and 2024.

The founder and CEO of AP International, Russian national Artur Paranyants, is also a member of the supervisory board for Slavyansk Eco LLC, which is owned by two brothers who share his surname. Before the 2022 invasion, the two partner companies appeared to be related as well: Archived versions of AP International’s website show that it used to share a logo with Slavyansk Eco and other companies in the Paranyants group.

Nonetheless, according to trade data, Slavyansk Eco continued to ship oil products, including gasoline, to AP International after these changes. In just the first four months of 2024, AP International imported at least 108 shipments.

At least 19 of those were marked for Malta, too.

A new sanctions landscape

The legal gray areas of the Russian oil embargoes and price cap have made enforcement an enduring challenge, experts agreed. The international response to the invasion appears to have applied enough pressure to lead some brokers to hide their Russian oil trading online—but maybe not enough to end it.“It is clear that the authorities acknowledge and understand that there is risk of sanctions avoidance and/or circumvention and that they are making efforts to address that,” Neale, the HFW senior associate, had said. But the emergence of new traders in Russian oil since the embargoes, he added, made for “a kind of multiheaded Hydra.”

Now, the U.S., EU and U.K. have taken aim at three of Russian oil’s heads with their designations of Rosneft, Lukoil and Gazprom Neft.

It was just the escalation that Donovan had advocated in her Atlantic Council piece from August, to give the West needed “leverage” on Putin.

“If the goal now is to get Putin to negotiate, then you need to hit him where it will still hurt,” Donovan told The Brief. “And right now, oil will hurt.”