Western countries have condemned what rights groups and U.N. officials describe as a brutal crackdown on protesters in Iran, where tens of thousands of people took to the streets and security forces responded with lethal force. The U.S. this week imposed new sanctions on Iranian officials tied to the suppression, while the United Nations has expressed “horror” at the scale of the violence, urging that “the killing of peaceful demonstrators must stop.”

As death-toll estimates stretch into the thousands, Iran's leadership has sought to justify its actions by labeling demonstrators as “terrorists” and blaming foreign powers for fomenting unrest. The government has cut internet access for more than a week, marking one of the country’s longest-ever blackouts, according to the cybersecurity watchdog NetBlocks.

International support appears to have played a role. Tehran's longstanding security relationship with Beijing—spanning police training, “counterterrorism” cooperation and surveillance technology—offers insight into how Iranian authorities both prepared their aggressive approach to dissent internally and how they have characterized it publicly.

As death-toll estimates stretch into the thousands, Iran's leadership has sought to justify its actions by labeling demonstrators as “terrorists” and blaming foreign powers for fomenting unrest. The government has cut internet access for more than a week, marking one of the country’s longest-ever blackouts, according to the cybersecurity watchdog NetBlocks.

International support appears to have played a role. Tehran's longstanding security relationship with Beijing—spanning police training, “counterterrorism” cooperation and surveillance technology—offers insight into how Iranian authorities both prepared their aggressive approach to dissent internally and how they have characterized it publicly.

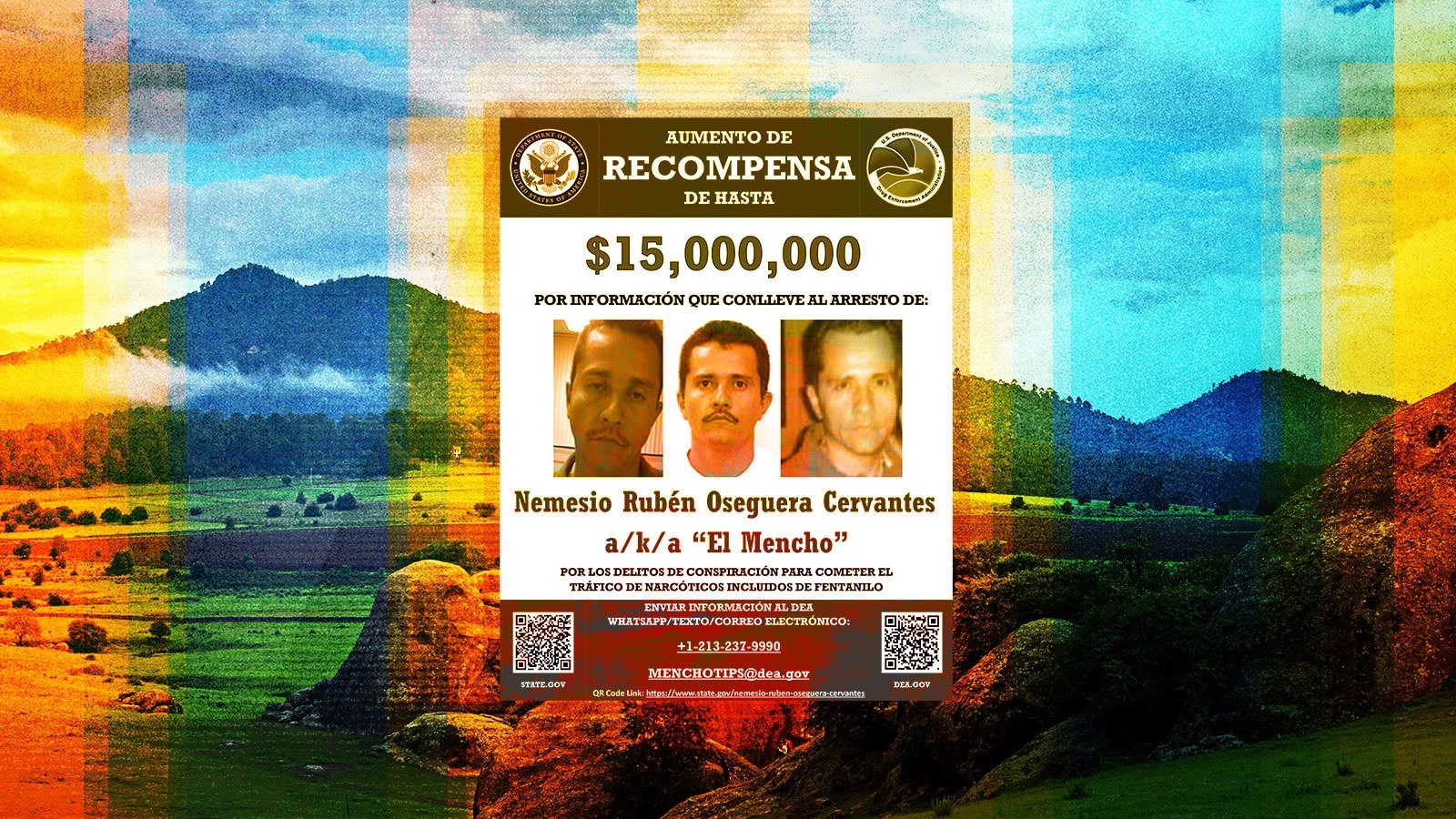

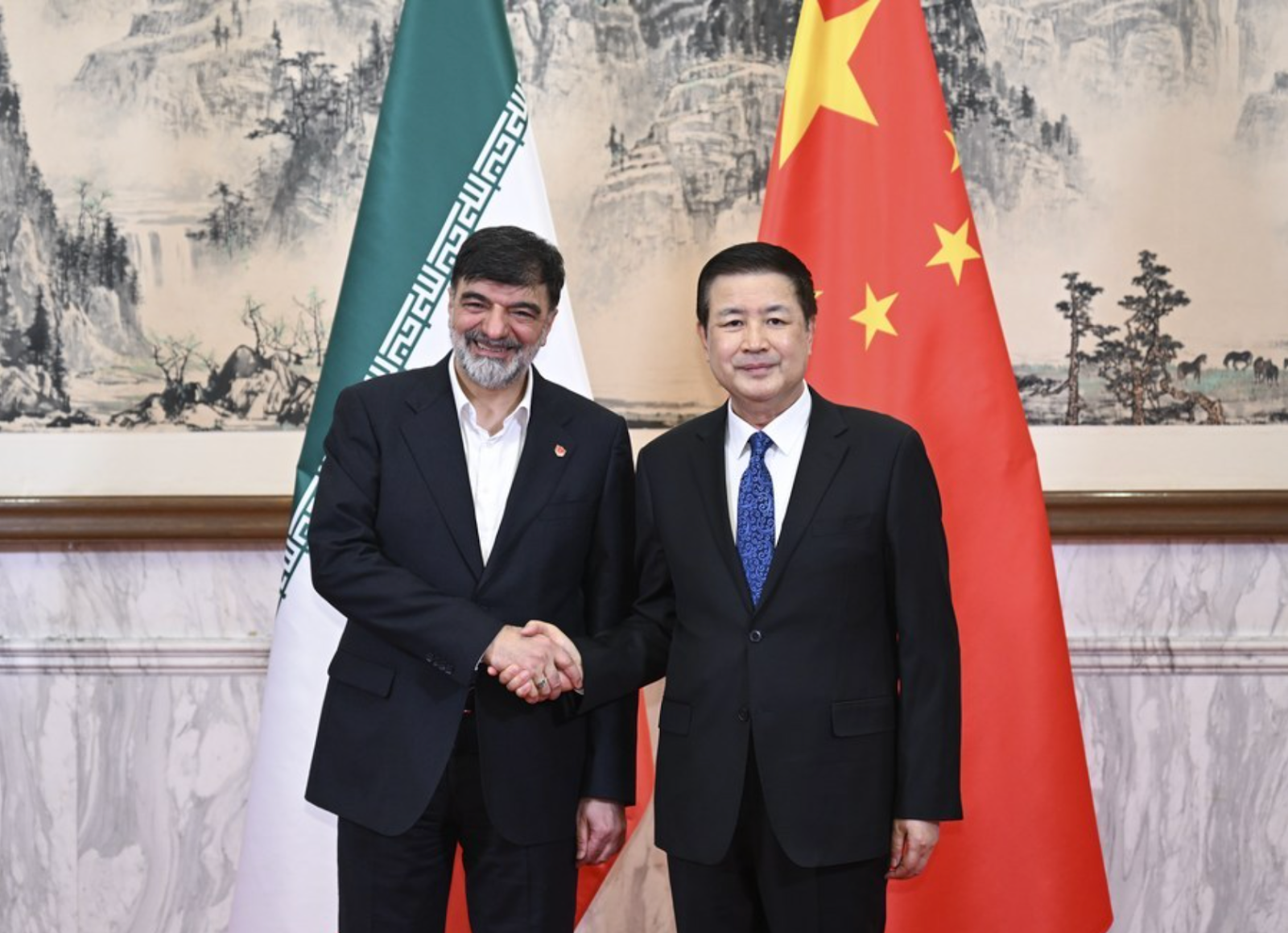

The Police Chief

Iranian Police Chief Ahmad-Reza Radan, left, meets with Chinese Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong in Beijing in January 2024. (Xinhua)

Ahmad-Reza Radan, Iran’s police chief and a vocal supporter of employing force against protesters, is leading the current state clampdown. His roles in previous ones led to Western sanctions.

The relationship remains active. On December 25, 2025, just days before Iran’s protests erupted, its ambassador to China visited the People’s Public Security University, pledging to continue “pragmatic cooperation in law enforcement and security,” according to a school press release.

- The U.S. sanctioned Radan for human rights abuses in 2010, when he was deputy chief of the National Police, calling him “responsible for beatings, murder, and arbitrary arrests and detentions against protestors that were committed by the police forces.” It then sanctioned him again in 2011 for his role in repressing dissent in neighboring Syria.

- The EU sanctioned Radan in 2020, citing the same repressive actions the U.S. cited in 2010.

- The agreement with China followed a similar public security pact between Tehran and Moscow, signed in 2023. According to IRNA, that agreement called for “the expansion of security and law enforcement cooperation and the exchange of experiences in dealing with factors that foment insecurity.”

The Training Pipeline

The People’s Public Security University of China, the country’s top police academy, has run “Advanced Iranian Police Officers Training Programs” since 2015, organized by China’s Ministry of Public Security, according to Chinese school materials and state media reports reviewed by Kharon. Such Iranian cooperation appears to have deepened since, and in 2018, Iran’s National Police University signed a formal agreement institutionalizing more exchange and training programs.The relationship remains active. On December 25, 2025, just days before Iran’s protests erupted, its ambassador to China visited the People’s Public Security University, pledging to continue “pragmatic cooperation in law enforcement and security,” according to a school press release.

Iran’s ambassador to China, Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, visits the People’s Public Security University of China. (People’s Public Security University of China)

What China teaches carries influence. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think tank based in Washington, D.C., reported in November that China uses such police trainings to export its domestic “stability maintenance” expertise, which it has most prominently applied in Xinjiang, also in the name of “counterterrorism.” The trainings, the Carnegie Endowment said, often come bundled with business opportunities for Chinese surveillance firms.

Its equipment, which flows through sales agents into a country where surveillance technology has reportedly been used to monitor the protests and track dissidents, offers one link between China’s security industry and Tehran’s monitoring capabilities.

Background: Tiandy Technologies says on its website that it has worked in China's public security sector for more than 20 years, serving clients including the Ministry of Public Security, which awarded it a first-class science and technology award in 2018.

The U.S. added Tiandy to the Entity List in 2022, citing its roles both in surveilling Muslim minorities in Xinjiang and in “enabling the procurement of U.S.-origin items for use by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.” In 2023, the Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. officials were considering additional sanctions on Chinese surveillance companies, including Tiandy, as Tehran increasingly relied on monitoring technology to suppress protests. Tiandy's products had been sold to IRGC units, the Journal said.

The China-Exported Surveillance Network

Tiandy Technologies, a Chinese provider of video surveillance tech, has built deep roots in Iran—and in China’s security establishment.Its equipment, which flows through sales agents into a country where surveillance technology has reportedly been used to monitor the protests and track dissidents, offers one link between China’s security industry and Tehran’s monitoring capabilities.

Background: Tiandy Technologies says on its website that it has worked in China's public security sector for more than 20 years, serving clients including the Ministry of Public Security, which awarded it a first-class science and technology award in 2018.

The U.S. added Tiandy to the Entity List in 2022, citing its roles both in surveilling Muslim minorities in Xinjiang and in “enabling the procurement of U.S.-origin items for use by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.” In 2023, the Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. officials were considering additional sanctions on Chinese surveillance companies, including Tiandy, as Tehran increasingly relied on monitoring technology to suppress protests. Tiandy's products had been sold to IRGC units, the Journal said.

Connecting the dots: Kharon research traced Tiandy’s Iran-facing sales network through Iranian entities tied to the brand:

The letter, published by the news site Roydad24, said that Tehran Mayor Alireza Zakani had planned contracts, including a €400 million purchase of smart cameras, with “unnamed” Chinese companies that had no internet presence. According to the Independent, municipality documents identified one vendor as “Tidndy”—a name that yielded no search results but appeared to be a misspelling of Tiandy.

“We hope the Iranian government and people will overcome the current difficulties and uphold stability in the country,” a Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman said at a press briefing Wednesday. China opposes, she added, “external interference in other countries’ internal affairs.”

John Krzyzaniak contributed research to this report.

Read more from the Kharon Brief:

- Tiandy Center is a subsidiary of Iran-based Ati Negar Basir Elektronik Company and a self-described “distributor of Tiandy Products.” An archived version of its website from July 2025 listed 18 offices across Iran and advertised that if a company becomes a Tiandy representative in Iran, it can also represent other Chinese video-surveillance brands, including Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd. and Zhejiang Dahua Technology Co., Ltd. The U.S. added both those companies to the Entity List in 2019, citing their roles in China’s repression and “high-technology surveillance” of minorities, and it later designated both as companies in China’s military industrial complex.

- Elm va Sanat Hafez Gostar Company is another distributor of Tiandy products in Iran. According to an archived version of its website from last month, the company listed Iranian government entities as its customers, including the Iran Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and the national traffic police. In addition to Tiandy products, Elm va Sanat Hafez Gostar also said it was a representative for Hangzhou Hikvision and Zhejiang Dahua.

The letter, published by the news site Roydad24, said that Tehran Mayor Alireza Zakani had planned contracts, including a €400 million purchase of smart cameras, with “unnamed” Chinese companies that had no internet presence. According to the Independent, municipality documents identified one vendor as “Tidndy”—a name that yielded no search results but appeared to be a misspelling of Tiandy.

The Messaging

In response to Iran’s protests and crackdown, China has staked out a clear public position: for its security and trading partner’s “stability” and against U.S. intervention.“We hope the Iranian government and people will overcome the current difficulties and uphold stability in the country,” a Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman said at a press briefing Wednesday. China opposes, she added, “external interference in other countries’ internal affairs.”

John Krzyzaniak contributed research to this report.

Read more from the Kharon Brief: