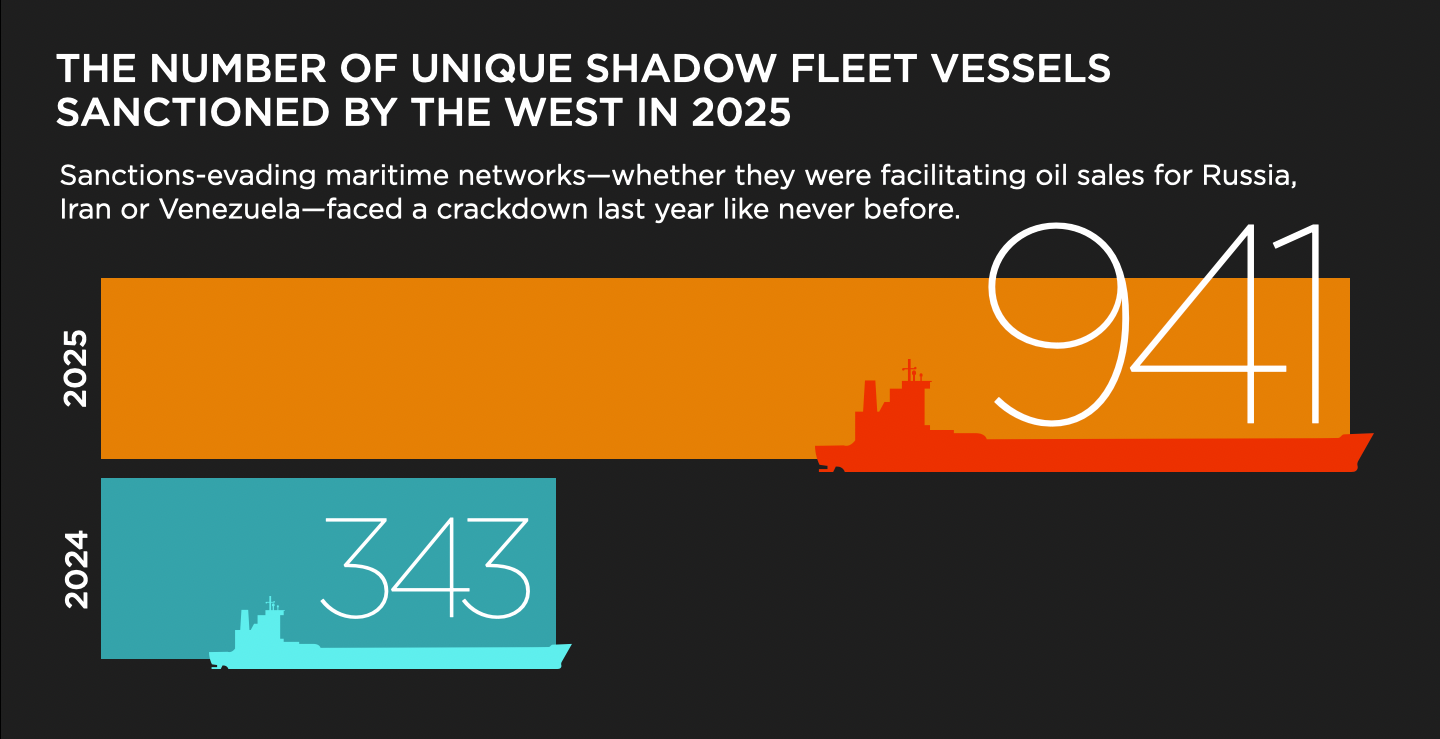

The West’s campaign against the “shadow fleet” that helps Iran, Russia and Venezuela dodge oil sanctions had already intensified last year. Then, around the world, ship seizures started spreading.

In January, after instituting a “blockade” on sanctioned oil tankers traveling in and out of Venezuela, the U.S. detained the Russia-flagged Marinera in the North Atlantic, with British support. Soon after, the French Navy detained the Grinch in the Mediterranean. Even India, which became a significant importer of Russian crude after Western sanctions hit, this month seized three tankers off its coast that the U.S. had sanctioned for shipping Iranian oil.

More pressure measures are in the works: The EU’s proposal for its 20th sanctions package against Russia notably would sanction dozens more shadow-fleet vessels and institute a full maritime services ban for Russian crude, while a bill advancing in the U.S. Senate would force reams of additional sanctions on ships and the ports that serve them.

In January, after instituting a “blockade” on sanctioned oil tankers traveling in and out of Venezuela, the U.S. detained the Russia-flagged Marinera in the North Atlantic, with British support. Soon after, the French Navy detained the Grinch in the Mediterranean. Even India, which became a significant importer of Russian crude after Western sanctions hit, this month seized three tankers off its coast that the U.S. had sanctioned for shipping Iranian oil.

More pressure measures are in the works: The EU’s proposal for its 20th sanctions package against Russia notably would sanction dozens more shadow-fleet vessels and institute a full maritime services ban for Russian crude, while a bill advancing in the U.S. Senate would force reams of additional sanctions on ships and the ports that serve them.

A U.S. Coast Guard ship accompanies the sanctioned oil tanker Marinera off the coast of Scotland on Jan. 14. U.S. forces had first tried to seize the ship in December, off the coast of Venezuela. (Peter Summers/Getty Images)

The Brief wanted to take a step back. Why is the crackdown on the shadow fleet escalating, how does the fleet operate and what else might the West do to sink it? To answer, we turned to four experts:

Some responses have been lightly edited for context.

The Brief: The West blitzed Russia’s shadow fleet with more than 900 sanctions in 2025. Now, EU countries and the U.S. are seizing sanctioned tankers, and the U.K. is exploring the legal framework to do the same. What’s changed, and should we be seeing this as the West’s new enforcement normal?

Donovan and Nikoladze: The shadow fleet has been one of the key elements of sanctions evasion used by Russia, Iran, and Venezuela. However, more recently, it has become a broader hazard to maritime safety and coastal states.

These vessels often operate under false flags, lack proper insurance, and pose higher risks of spills, collisions and abusive labor conditions for crews—making global shipping less safe.

Barresi: What’s new is a greater push by port authorities and similar bodies to create a legal basis for detention of suspect vessels, [as] the shadow fleet is being reframed as a security and rule-of-law issue.

Handley: In the TV show “The West Wing,” there’s an episode where a tanker is carrying oil in breach of UN sanctions. The president knows the money from selling the oil will outweigh any fine. He says: “If we’re going to have sanctions at all, I think we should make them stick. I think that we should confiscate the cargo, seize the ship, sell the oil and use the money to beef up anti-smuggling operations.”

While tempting, that is not yet the law (in the U.K. and EU). Seizures of tankers and other vessels have been done in 2024 (Germany), 2025 (France and Estonia) and 2026 (Finland and France). In every case, however, the vessel and crew have been released with the cargo intact.

As the law stands, in Europe, foreign-flagged vessels in international waters are, by definition, not committing a sanctions offense.

Donovan and Nikoladze: Whether tanker seizures become a new enforcement normal for the West depends largely on whether the legality of these actions can be proven, and whether sanctioning authorities can determine what to do with the tankers after seizing them. Court proceedings can take several months or even years to conclude, and the cost of maintaining these tankers during that time is another significant hurdle.

Thus, while tanker seizures immediately halt sanctioned and hazardous activity, legal challenges and logistical hurdles around custody, upkeep and disposal of seized tankers remain key questions for future enforcement.

Barresi: I’d expect more territorial-water/port detentions and challenges to vessels that fall under these and similar violations. But I doubt we’ll see routine high-seas seizures.

Handley: The short-lived seizures [to date] have achieved a few headlines but nothing else.

- Mark Handley, a U.K.-based partner at the international law firm Duane Morris;

- Kimberly Donovan, director of the Economic Statecraft Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center, and Maia Nikoladze, its associate director;

- and Joseph Barresi, a research director at Kharon.

Some responses have been lightly edited for context.

The Brief: The West blitzed Russia’s shadow fleet with more than 900 sanctions in 2025. Now, EU countries and the U.S. are seizing sanctioned tankers, and the U.K. is exploring the legal framework to do the same. What’s changed, and should we be seeing this as the West’s new enforcement normal?

Donovan and Nikoladze: The shadow fleet has been one of the key elements of sanctions evasion used by Russia, Iran, and Venezuela. However, more recently, it has become a broader hazard to maritime safety and coastal states.

These vessels often operate under false flags, lack proper insurance, and pose higher risks of spills, collisions and abusive labor conditions for crews—making global shipping less safe.

Barresi: What’s new is a greater push by port authorities and similar bodies to create a legal basis for detention of suspect vessels, [as] the shadow fleet is being reframed as a security and rule-of-law issue.

Handley: In the TV show “The West Wing,” there’s an episode where a tanker is carrying oil in breach of UN sanctions. The president knows the money from selling the oil will outweigh any fine. He says: “If we’re going to have sanctions at all, I think we should make them stick. I think that we should confiscate the cargo, seize the ship, sell the oil and use the money to beef up anti-smuggling operations.”

While tempting, that is not yet the law (in the U.K. and EU). Seizures of tankers and other vessels have been done in 2024 (Germany), 2025 (France and Estonia) and 2026 (Finland and France). In every case, however, the vessel and crew have been released with the cargo intact.

As the law stands, in Europe, foreign-flagged vessels in international waters are, by definition, not committing a sanctions offense.

Donovan and Nikoladze: Whether tanker seizures become a new enforcement normal for the West depends largely on whether the legality of these actions can be proven, and whether sanctioning authorities can determine what to do with the tankers after seizing them. Court proceedings can take several months or even years to conclude, and the cost of maintaining these tankers during that time is another significant hurdle.

Thus, while tanker seizures immediately halt sanctioned and hazardous activity, legal challenges and logistical hurdles around custody, upkeep and disposal of seized tankers remain key questions for future enforcement.

Barresi: I’d expect more territorial-water/port detentions and challenges to vessels that fall under these and similar violations. But I doubt we’ll see routine high-seas seizures.

Handley: The short-lived seizures [to date] have achieved a few headlines but nothing else.

(Kharon illustration / Adobe Stock Images)

The Brief: We know that the Russian, Venezuelan and Iranian fleets overlap with each other. The U.S., in one recent example, seized the Marinera, which it had sanctioned in 2024 for facilitating Hizballah, while it was coming from Venezuela and flying a Russian flag. What do cases like that tell us about the structure of these networks and how they operate?

Barresi: These networks operate less as separate national fleets and more as a shared sanctions-evasion services ecosystem that advances the converging interests of these three states and their allies. Their vessels encompass an interwoven fleet run through a web of owners, facilitators and ship-management companies.

This is also not a new phenomenon: We’ve seen for over a decade cases where a vessel has been engaged in illicit activities touching across various sanctions regimes.

Donovan and Nikoladze: Frequent flag-hopping is one of the defining features of how the shadow fleet operates.

Throughout 2025, over 70 percent of sanctioned vessels changed flags to obscure ownership and complicate enforcement efforts. In the coming months, an estimated 120 shadow fleet tankers are expected to reflag to Russia’s registry, as it is effectively one of the few jurisdictions still willing to accept them. Under international maritime law, a Russian flag can offer formal legal protection and is intended to reduce the risk of seizure at sea.

Handley: There is no question that the ownership structures adopted to own and operate the vessels can be complex, multi-layered and opaque.

It is also the case that such vessels can be available for charter. Different charterers, with different needs, and seeking to avoid the prohibitions under a variety of different sanctions regimes, can charter the same vessel and benefit from the same opaque structures.

The rules and regulations in place are not as adept as the vessels are at moving across regimes. A power against a sanctioned vessel under the Russian regulations does not extend to enforcing a breach of a prohibition under the Iran sanctions. More could be done to adopt a holistic approach to such powers and enforcement.

The Brief: The shadow fleet encompasses hundreds of oil tankers and shuffling parent companies registered in jurisdictions around the world. What risks or challenges has it created for legitimate business operations, and what kinds of red flags should businesses look out for?

Barresi: The shadow fleet makes ordinary maritime commerce unusually risky by turning routine touchpoints—chartering, insurance, port calls, trade finance—into sanctions, safety and liability traps.

Barresi: These networks operate less as separate national fleets and more as a shared sanctions-evasion services ecosystem that advances the converging interests of these three states and their allies. Their vessels encompass an interwoven fleet run through a web of owners, facilitators and ship-management companies.

This is also not a new phenomenon: We’ve seen for over a decade cases where a vessel has been engaged in illicit activities touching across various sanctions regimes.

Donovan and Nikoladze: Frequent flag-hopping is one of the defining features of how the shadow fleet operates.

Throughout 2025, over 70 percent of sanctioned vessels changed flags to obscure ownership and complicate enforcement efforts. In the coming months, an estimated 120 shadow fleet tankers are expected to reflag to Russia’s registry, as it is effectively one of the few jurisdictions still willing to accept them. Under international maritime law, a Russian flag can offer formal legal protection and is intended to reduce the risk of seizure at sea.

Handley: There is no question that the ownership structures adopted to own and operate the vessels can be complex, multi-layered and opaque.

It is also the case that such vessels can be available for charter. Different charterers, with different needs, and seeking to avoid the prohibitions under a variety of different sanctions regimes, can charter the same vessel and benefit from the same opaque structures.

The rules and regulations in place are not as adept as the vessels are at moving across regimes. A power against a sanctioned vessel under the Russian regulations does not extend to enforcing a breach of a prohibition under the Iran sanctions. More could be done to adopt a holistic approach to such powers and enforcement.

The Brief: The shadow fleet encompasses hundreds of oil tankers and shuffling parent companies registered in jurisdictions around the world. What risks or challenges has it created for legitimate business operations, and what kinds of red flags should businesses look out for?

Barresi: The shadow fleet makes ordinary maritime commerce unusually risky by turning routine touchpoints—chartering, insurance, port calls, trade finance—into sanctions, safety and liability traps.

A single falsified document or hidden connection can trigger sanctions exposure, payment failures, detentions, and even denied P&I coverage, which then cascades into disputes and costly audits. Because many shadow-fleet tankers are older and operate outside standard compliance, the risk of collisions or spills—and uncertainty over who pays—rises. Heightened port scrutiny also means more delays.

Donovan and Nikoladze: Financial institutions are advised to watch for red flags such as companies with limited trading history handling large volumes of oil, registrations in high-risk jurisdictions or a lack of public information on ownership.

Further, according to the Price Cap Coalition advisory, maritime industry stakeholders should report on ships that trigger concerns to help authorities promote safety in shipping. Private actors involved in the sale and brokering of tankers should conduct due diligence, especially when selling older vessels, and obtain documents showing buyers’ beneficial owners. Once obtained, these documents should be verified against third-party databases and media sources. They are also encouraged to develop training programs for employees to identify red flags and sanctions risks.

Barresi: Businesses should be wary of vessels when their movements include activities such as AIS spoofing, unusual routing or ship-to-ship transfers. Sudden reflagging and weak insurance should also trigger alarms.

Handley: It is worth remembering the limited legal impact that comes when the U.K. “specifies” a ship under its Russian sanctions: It may be barred from entering a U.K. port, or it may be required to enter or stay at a U.K. port or otherwise be given a “movement direction.”

That’s it. There is no prohibition on doing business with such ships, or transporting cargo through such ships, or against buying or selling cargo carried by such ships. There may be prohibitions in place in relation to that cargo (or the ship owners, or the buyers and sellers) but not for the vessel itself.

Despite this, the U.K. has started to include “dealing with U.K.-specified ships” as part of the basis for sanctioning people and entities. As such, it would be wise to screen vessels and their IMOs and to treat old vessels and recently acquired and/or opaque ownership as red flags to be escalated and resolved.

Donovan and Nikoladze: All of these requirements make private companies the tip of the spear in sanctions enforcement.

Donovan and Nikoladze: Financial institutions are advised to watch for red flags such as companies with limited trading history handling large volumes of oil, registrations in high-risk jurisdictions or a lack of public information on ownership.

Further, according to the Price Cap Coalition advisory, maritime industry stakeholders should report on ships that trigger concerns to help authorities promote safety in shipping. Private actors involved in the sale and brokering of tankers should conduct due diligence, especially when selling older vessels, and obtain documents showing buyers’ beneficial owners. Once obtained, these documents should be verified against third-party databases and media sources. They are also encouraged to develop training programs for employees to identify red flags and sanctions risks.

Barresi: Businesses should be wary of vessels when their movements include activities such as AIS spoofing, unusual routing or ship-to-ship transfers. Sudden reflagging and weak insurance should also trigger alarms.

Handley: It is worth remembering the limited legal impact that comes when the U.K. “specifies” a ship under its Russian sanctions: It may be barred from entering a U.K. port, or it may be required to enter or stay at a U.K. port or otherwise be given a “movement direction.”

That’s it. There is no prohibition on doing business with such ships, or transporting cargo through such ships, or against buying or selling cargo carried by such ships. There may be prohibitions in place in relation to that cargo (or the ship owners, or the buyers and sellers) but not for the vessel itself.

Despite this, the U.K. has started to include “dealing with U.K.-specified ships” as part of the basis for sanctioning people and entities. As such, it would be wise to screen vessels and their IMOs and to treat old vessels and recently acquired and/or opaque ownership as red flags to be escalated and resolved.

Donovan and Nikoladze: All of these requirements make private companies the tip of the spear in sanctions enforcement.

(Kharon illustration / Adobe Stock Images)

The Brief: The EU is now proposing to ban all maritime services for Russian crude. In August, Panama outlawed the registration of any vessels over 15 years old, on the basis that older tankers are more likely to be involved in the shadow fleet. Are more creative approaches like these, beyond sanctions, needed to break up the fleet and cut off its illicit oil exports?

Handley: It does look more and more like alternative options to the “oil price cap” are being explored. The oil price cap was designed to allow lawful trading in discounted Russian oil, but the time for such measures may be running out. The U.K. and U.S. have sanctioned the Russian “oil majors” Rosneft and Lukoil, and the EU Commission has proposed an alternative maritime services ban on the Russian oil sector. We’ll see if that survives the EU’s negotiation process and in what form.

As to Panama’s action, if its steps are not replicated by other registries, it won’t have much impact. It sends a signal from Panama, but it reduces the pool of available convenience registries by only one. Meaningful action requires coordination at the international level.

Barresi: The shadow fleet functions less like a fixed list of sanctioned ships and more like an adaptive logistics system that can swap flags, insurers, managers and paper ownership faster than sanctions lists can keep up. That’s why operating-environment measures are increasingly important.

Donovan and Nikoladze: [More creative approaches are needed], especially if environmental levers are used and the shadow fleet is framed not only as a sanctions-evasion mechanism but also as a pollution and maritime safety threat. This framing broadens the coalition for action. Organizations such as the International Maritime Organization and the International Labor Organization should be directly involved, given deceptive recruitment practices affecting shadow fleet crews.

At the same time, improving maritime sanctions enforcement remains essential. A key obstacle is beneficial ownership transparency. The fleet can keep expanding—despite vessel seizures—if sellers cannot identify sanctioned actors hidden behind complex ownership structures. The Financial Action Task Force has been recommending that member states ensure competent authorities can access information on companies’ true owners.

Making this data available would reduce inadvertent sales to sanctioned entities and close a major loophole in maritime sanctions enforcement.

Read more from The Brief:

Handley: It does look more and more like alternative options to the “oil price cap” are being explored. The oil price cap was designed to allow lawful trading in discounted Russian oil, but the time for such measures may be running out. The U.K. and U.S. have sanctioned the Russian “oil majors” Rosneft and Lukoil, and the EU Commission has proposed an alternative maritime services ban on the Russian oil sector. We’ll see if that survives the EU’s negotiation process and in what form.

As to Panama’s action, if its steps are not replicated by other registries, it won’t have much impact. It sends a signal from Panama, but it reduces the pool of available convenience registries by only one. Meaningful action requires coordination at the international level.

Barresi: The shadow fleet functions less like a fixed list of sanctioned ships and more like an adaptive logistics system that can swap flags, insurers, managers and paper ownership faster than sanctions lists can keep up. That’s why operating-environment measures are increasingly important.

Donovan and Nikoladze: [More creative approaches are needed], especially if environmental levers are used and the shadow fleet is framed not only as a sanctions-evasion mechanism but also as a pollution and maritime safety threat. This framing broadens the coalition for action. Organizations such as the International Maritime Organization and the International Labor Organization should be directly involved, given deceptive recruitment practices affecting shadow fleet crews.

At the same time, improving maritime sanctions enforcement remains essential. A key obstacle is beneficial ownership transparency. The fleet can keep expanding—despite vessel seizures—if sellers cannot identify sanctioned actors hidden behind complex ownership structures. The Financial Action Task Force has been recommending that member states ensure competent authorities can access information on companies’ true owners.

Making this data available would reduce inadvertent sales to sanctioned entities and close a major loophole in maritime sanctions enforcement.

Read more from The Brief: